Saturday, November 29, 2014

LERMONTOV AND GOGOL

The year 2014 marks the two-hundredth anniversary of Mikhail Lermontov's birth. So all over the Russian-speaking world people are getting together to commemorate his short life and to read his poetry.

It is always interesting to contemplate meetings between great writers, to consider what they may have said to one another. In 1878 Tolstoy and Dostoevsky sat in the same lecture hall, listening to a talk by Solovyov. They never met, not that day or any other, but if they had the fur surely would have flown.

Here are three great Russian writers, Lermontov, Pushkin, and Gogol, pictured in confabulation, as part of the mammoth Monument to A Thousand Years of Russian History, in Great Novgorod. Such a confabulation never took place, as the three of them never got together. Gogol and Pushkin, however, did know each other, although they were not great friends, and Pushkin provided Gogol with the plots for some of his most famous works.

Lermontov and Gogol met only twice, on two successive days in Moscow, May 9 and May 10, 1840. Lermontov showed up for a party commemorating Gogol's nameday on May 9. It was held in the gardens of the historian and publicist Pogodin, with whom Gogol was lodging at the time. The next day they met again, at a gathering hosted by E.A. Sverbeeva.

On that spring in 1840 Gogol was the most renowned Russian writer of the time, and Lermontov, already highly respected for his verse, had just published the best early realistic novel in Russian literature (A Hero of Our Time).

Each of them was on the way somewhere else at the time they met. Gogol was soon off back to his beloved Rome, while Lermontov, still in the army and exiled from St. Petersburg for his unruly ways, was bound for the Caucasus, where he would be killed in a duel a year later.

What did they say to each other when they met? Nobody knows. Apparently nothing of much interest, since neither of the two writers recorded a single word of that conversation.

Thursday, November 20, 2014

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

UNOFFICIAL "MUSEUM" OF "THE MASTER AND MARGARITA" at Apt. No. 50 in Moscow

Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita features the story of Satan's visit to Moscow in the time of Stalin. It also retells the story of the passion of Jesus Christ:

"Immortality. . . It's come now, immortality."

Begemot, the Black Tomcat of "Master and Margarita." The name means literally "hippopotamus," and is usually translated by translators of Bulgakov as "Behemoth."

N.Y. Times Travel section, Nov. 13, 1994

The first floor of Bldg. No. 10, Bol'shaja Sadovaja St. in Moscow is the site of the Museum-Theater of the Bulgakov House. Since May of 2007 there has been a second museum in the building. It is called The State Museum of M.A. Bulgakov and is located in Apt. No. 50 upstairs.

Bulgakov himself once lived in Apt. 50 (beginning in Sept., 1921), and, in writing his brilliant novel, The Master and Margarita, he used the apartment as prototype for the place occupied by the devil (Woland) and his henchmen (Apt. 302)--including the most popular character in the story, the huge black tomcat called Begemot--during their visit to Moscow. Patriarch Ponds, the little park where Woland makes his first appearance in the novel, is located nearby.

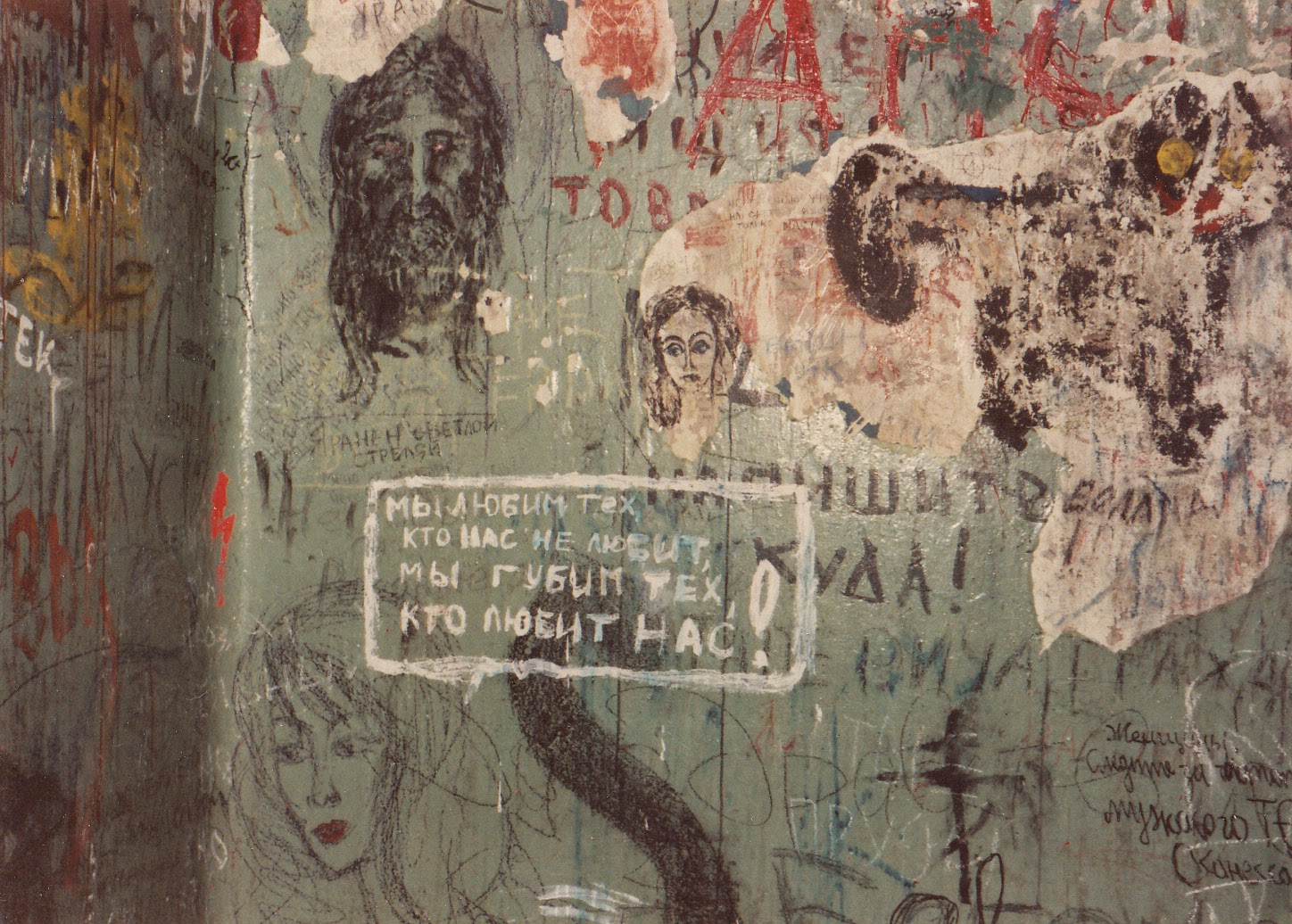

In the early nineties there were not yet any Bulgakov museums at the site, but there was a sort of unofficial "museum" of tributes to the novel in graffiti outside Apt. No. 50. During these times the apartment was still occupied, various efforts were made to keep sightseers and graffiti artists away, but they kept coming to "the apartment of the devil."

Here I am posting various photographs of the graffiti, some of it quite impressive artistically. I took these pictures in the summer of 1992 or 1993.

Mikhail Bulgakov:

"Master, I'm yours. Margo."

"We love those who don't love us; we destroy those who love us."

"Stop the world; I want to get off."

Woland (Satan) as pictured in his most devilish aspect:

Friday, November 7, 2014

What's it going to be then, eh? Translating Burgess' CLOCKWORK ORANGE into Russian

Translating Anthony Burgess' Clockwork Orange into Russian presents some rather unusual difficulties. When writing the novel in English, Burgess invented a slang-argot for his juvenile delinquents of the not-too-distant future. The argot is replete with Russian words, many of them jazzed up by Little Alex and his "droogies" (friends, from the Russian word друг).The translator V. Boshnyak could have attempted to do something similar, throwing words with English roots into the Russian text. This would have been a formidable task. So instead of doing this, he kept all Russian words for the text of his translation, but used the Latin alphabet, rather than Cyrillic, for the slangy words:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)