Tuesday, January 27, 2015

"Anna Karenina" EMOTIONS, INTUITION, UNSPOKEN COMMUNICATION, BODY LANGUAGE

(16) Rationality and Irrationality

In Tolstoy's time there were no computers reading human faces, puzzling out the furrows in our brows or the lack thereof (see previous posting: "Big Brother Wants to Know"), but Tolstoy seemed already to be an expert on how looks and smiles sometimes communicate better than words (see previous posting: "The Eyes and Smiles").

Russian writers of the nineteenth century often have a way of reasoning their way toward non-reasoning. In other words, they use a great deal of logical thought to arrive at the conclusion that the great truths of the universe are not rational, but intuitive.

The two greatest anti-rational rationalists--or to look at it from the other direction--rational anti-rationalists--of nineteenth century Russian literature are Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Certainly one of the best novels in this vein is "Anna Karenina." Note how often in this book that the characters are guided by emotions, rather than reason. A good deal of the communication between characters is wordless, and sometimes the most important decisions in people's lives come about through misinterpretation of bodily language, or through a reliance on anything but logic.

Late in the book, e.g., Anna's and Karenin's lives are influenced by Karenin's acceptance of a quack, the spiritual medium (Landau), and the hyper-rationalist Koznyshev lets emotions and mushrooms distract him from the rational speech of proposal that he is about to proclaim.

Reasoning does not seem to lead to solutions of life's problems, nor does philosophizing (which is a kind of deep abstract reasoning). Lyovin agonizes all through the novel, attempting to reason his way to truth, but he ends up deciding that the instinctive life of the non-reasoning peasant is the best truth of all:

"Isn't it distinctly to be seen in the development of each philosopher's theory that he knows what the chief significance of life is beforehand, just as positively as the peasant Fyodor and not a bit more clearly than he, and is simply trying but a dubious intellectual path to come back to what everyone knows?" (832). Of course, Lyovin is Tolstoy's alter ego, and both his struggles to understand life through reading the great philosophers and his ultimate conclusion that the illiterate peasant knows best after all are Tolstoy's own conclusions.

In "Anna Karenina" people do not act very reasonably, even when it may be in their best interests to do so. Toward the end of their life together Anna and Vronsky are involved in continuous destructive quarrels, which some outside evil force seems to promote, and which they carry on even when they are aware that they are destroying one another. Here Tolstoy seems to be suggesting that there are many things more important in motivating human behavior than logic and reason.

Lyovin's (Tolstoy's own) desire to abandon reason and find some "natural," non-thinking, intuitive truth (usually in communion with nature or the earth) is nothing new in Russian literature, or in world literature for that matter. In the twentieth century, e.g., Solzhenitsyn--much influenced by Tolstoy--perpetuated this ancient idea.

All of this, however, in wrapped up in a huge contradiction (the very contradiction of Lyovin in "AK"), since an intellectual, a thinker, arrives--through or by means of thought-- at the idea of negation of thought. It also, of course, can be a very dangerous thing, since denigration of reason and exaltation of human "natural" animality is just a step away from admiring beastliness and amorality, even chaos. The great twentieth-century short-story writer, Isaac Babel, got himself rather badly involved in this disturbing contradiction, when he wrote his Red Cavalry stories.

Here are several examples of how important a role unvoiced communication plays in "AK":

(1) Examples where one character misinterprets another's thoughts by "reading" body language

(a) When Anna tells Vronsky that she is pregnant with his child, while still married to Karenin, "a proud and stern expression came over his face.

"Yes, yes, that's better, a thousand times better! I know how painful it was," he said

"But she was not listening to his words, she was reading his thoughts from the expression on his face. She could not guess that the expression arose from the first idea that presented itself to Vronsky--that a duel was now inevitable. The idea of a duel had never crossed her mind, and so she put a different interpretation on this stern expression" (333).

(b) Lyovin watches Kitty in her conversation with Veslovsky. She is moved by his description of Anna's life, but Lyovin thinks she is in love with Veslovsky:

"He saw on his wife's face an expression of deep feeling as she gazed with fixed eyes on the handsome face of Vasenka" (598). This leads to an eruption of jealously and to Lyovin's decision to throw the young fop off his estate.

(2) Good examples of unspoken communication

(a) Before the beginning of their affair Anna and Vronsky are at a soiree, V. is pursuing A. and she is pleased despite herself. At one point she says, "That only shows you have no heart". . . . "But her eyes said that she knew he had a heart and that was why she was afraid of him" (148).

(b) Lyovin and Kitty in the scene already discussed (previous posting), when she is trying to spear a mushroom and talking about bears, but "her lips, her eyes and hands" are expressing all the significant things (405)

[Another good example of unspoken communication is to be found in Tolstoy's "The Death of Ivan Ilich," when the hero's brother-in-law comes for a visit, lays eyes for the first time on the sick man and says nothing. But his eyes are clearly saying, "You're a dead man."]

(3) Bad, rather unbelievable examples of unspoken communication

(a) Kitty and Varenka at the spa in Germany:

"The two girls used to meet several times a day, and every time they met Kitty's eyes said, 'Who are you? What are you? Are you really the exquisite creature I imagine you to be? But for goodness sake don't suppose,' her eyes added, 'that I would force my acquaintance on you; I simply admire you and like you.'

'I like you too, and you're very, very sweet. And I would like you better, still, if I had time,' answered the eyes of the unknown girl" (228).

The problem here is that eyes simply don't have such a big vocabulary!

(b) The scene of the writing with the chalk at the time of Lyovin's marriage proposal to Kitty (already discussed: see posting "Love and Mushrooms")

Monday, January 26, 2015

BIG BROTHER WANTS TO KNOW HOW YOU FEEL: COMPUTERS THAT READ HUMAN FACES (and THE RUSSIAN SLIT-EYED SQUINT)

There's a rather alarming article in Jan. 19, 2015 issue of "The New Yorker": Raffi Khatchadourian, "We Know How You Feel," p. 50-59.

The subject matter is how scientists are learning to create computers that read human emotions by studying facial expressions:

"Our faces are organs of emotional communication; by some estimates, we transmit more data with our expressions than with what we say, and a few pioneers dedicated to decoding this information have made tremendous progress. Perhaps the most successful is an Egyptian scientist living near Boston, Rana el Kaliouby. Her company, Affectiva, formed in 2009, has been ranked by the business press as one of the country's fastest-growing startups. . . "(50).

The software, Affdex, looks at everything when it examines a human face: "the shifting texture of skin, the distribution of wrinkles around an eye, or the furrow of a brow. . . The algorithm identifies an emotional expression by comparing it with countless others that it has previously analyzed" (52).

Affectiva builds on models created by a research psychologist, Paul Ekman, "who, beginning in the sixties, built a convincing body of evidence that there are at least six universal human emotions, expressed by everyone's face identically, regardless of gender, age, or cultural upbringing [my emphasis, URB]. Ekman compiled a Facial Action Coding System (FACS), which is widely used, e.g., by academics and police officers.

Computers now "outperform people in distinguishing social smiles from those triggered by spontaneous joy, and in differentiating between faked pain and genuine pain" (52).

Kaliouby and her colleague Rosalind Picard created the new field in computer science called "affective computing." In the early stages of their work their intentions were highly altruistic. Kaliouby, for example, worked on a project to help autistic patients better interpret human expressions. Her Mind Reader was a program that she hoped would "construct an 'emotional hearing aid' for people with autism. The wearer would carry a small computer, and earpiece, and a camera, to scan people's expressions. In gentle tones, the computer would indicate appropriate behavior: keep talking, or shift topics" (54).

But when the corporate world and the government found out about Mind Reader they swarmed around its inventors with inquiries. "Pepsi was curious if it could use the software to gauge consumer preferences. Bank of America was interested in testing it in A.T.M.s. Toyota wanted to see if it could better understand driver behavior" (56). And so on. And so on. You can bet that the CIA and NSA perked up their ears and antennas. FOX wanted to test all its pilot shows with this software; advertisers all and sundry were fascinated with the idea of using computer software to study a face, and to predict whether that face liked their product. Soon the good intentions and the altruistic impulses of the founder of this software were being stretched out into areas far from altruistic.

Affdex has now been so highly refined that it can "read the nuances of smiles better than most people can" (56). Now there are new projects to upgrade "the detection of furrowed eyebrows." Affdex ran tests on 80,000 brow furrows. Obviously, this computer program now knows infinitely more about brow furrows than anyone on earth.

So what next? The possibilities are rife. Emotion-sensing vending machines and A.T.M.s that would understand when users are in a relaxed mood and susceptible to advertising. Anheuser-Busch has designed a responsive beer bottle, because sports fans at games "wishing to use their beverage containers to express emotions are limited to, for example, raising a bottle to express solidarity with a team" (58).

Next, you suppose, will come the better, new and improved beer bottle with a built-in computer, to study your teeth for cavities and your brain for openings: places where a bit of advertising can intrude. Apple has recently come up with the iWatch, "which can measure heart rate and physical activity, and link these data to your location. The new products complement another line of Apple's research: mood-targeted advertising. . . With the new watch, they are going to know everything about you" (59).

Samsung is quoted as saying, "If we know the emotion of each user we can provide more personalized services" (59). This reminds me of the incessant message over the phone: "your call is being recorded to better serve you," which means, "to better serve us."

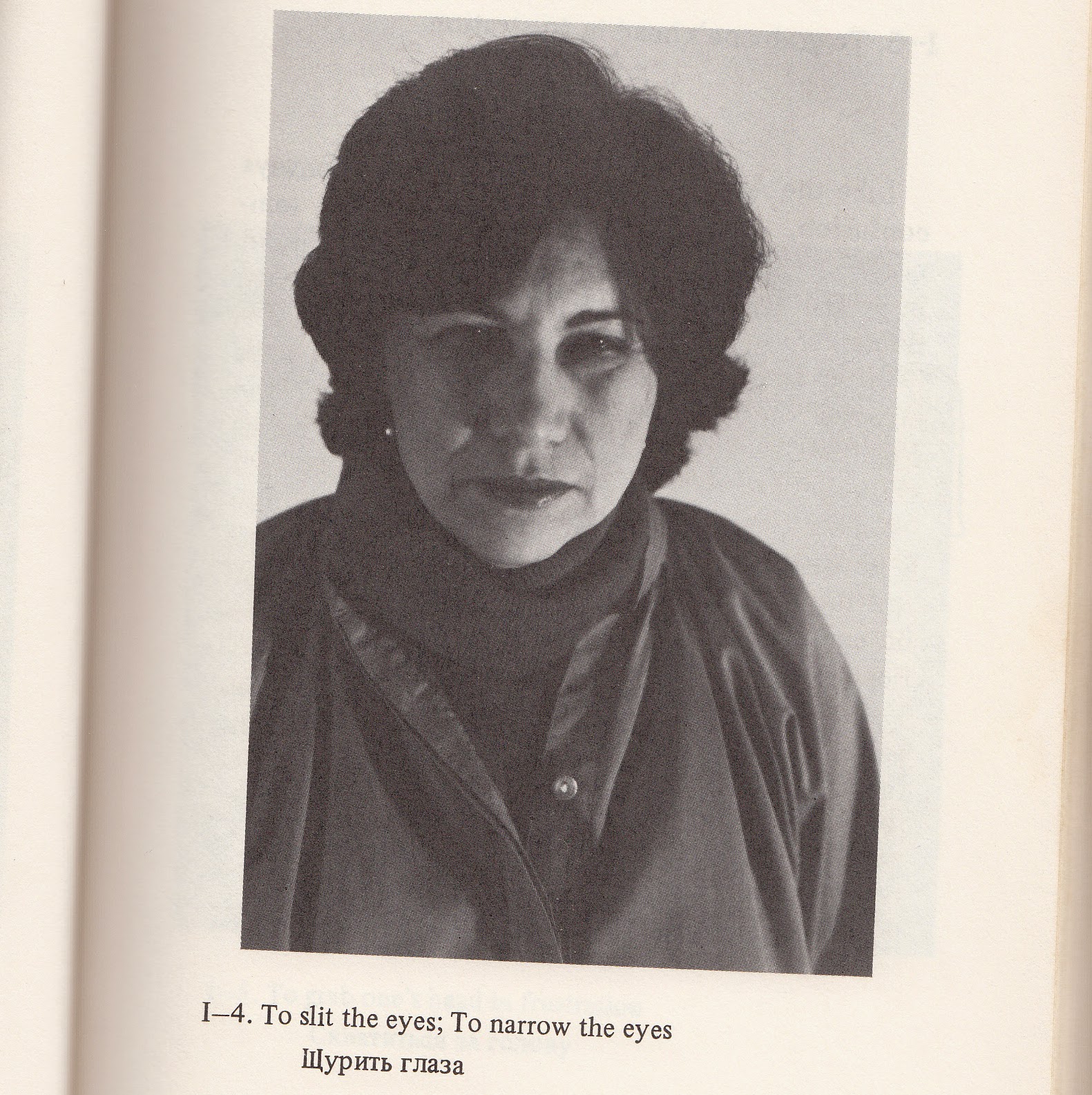

Pretty scary stuff, but, you may ask, what does this have to do with Russians or Russian literature? Well, quite a bit, as it so turns out. Take a look at this picture of a Russian face:

[from Barbara Monahan, A Dictionary of Russian Gesture (Hermitage Publications, 1983), p. 27.]

In describing this gesture, Monahan (p.26) cites Edmond Wilson's book, A Window on Russia, and Wilson mentions Anna Karenina's habitual gesture of narrowing her eyes in times of stress. Monahan writes that this gesture indicates, among other things, "I'm concentrating. I'm thinking what I should do next."

The other things (I think) are more important. The gesture, which probably originally came out of a fear of the evil eye, indicates apprehension. The person slitting his/her eyes is engaging in a defensive act, keeping intruding eyes out.

People other than Russians may also use this gesture, but, for example, I think that far fewer Americans do this slit-eyed squint than Russians do (with the possible exception of Clint Eastwood). It comes, largely, out of a thousand years of Russian paranoia.

Russians feel the constant need to protect themselves from hostile eyes. Russian simply do not trust very many people. They wear on their faces a habitual look of sour non-commitment, what Americans see as a frown. It's just not safe to open yourself up too much. In fact, Russians are firmly set against what they call "the American smile," which they consider something superfluous and frivolous. A Russian friend of mine, who has lived in the U.S. for years, walks around with his Russian look on his face, and Americans are constantly asking him, "Sergei, what's wrong?"

So what I'm wondering is this: could the Affdex computer software get anywhere looking at Russian faces? Could it look, say, at Vladimir Putin's face and figure out what he's feeling? Given that Putin wears not only the habitual Russian face mask, but also, on top of that, he wears the mask of the professional spook. So they say, he even sleeps with his spook mask on.

I don't know, but I'm guessing that the Affdex program would scream out for help if it had to deal with the Russian slit-eyed squint. What a shame for all the American mind-reading companies who would like to read Russian minds and make big money in the Russian market!

The subject matter is how scientists are learning to create computers that read human emotions by studying facial expressions:

"Our faces are organs of emotional communication; by some estimates, we transmit more data with our expressions than with what we say, and a few pioneers dedicated to decoding this information have made tremendous progress. Perhaps the most successful is an Egyptian scientist living near Boston, Rana el Kaliouby. Her company, Affectiva, formed in 2009, has been ranked by the business press as one of the country's fastest-growing startups. . . "(50).

The software, Affdex, looks at everything when it examines a human face: "the shifting texture of skin, the distribution of wrinkles around an eye, or the furrow of a brow. . . The algorithm identifies an emotional expression by comparing it with countless others that it has previously analyzed" (52).

Affectiva builds on models created by a research psychologist, Paul Ekman, "who, beginning in the sixties, built a convincing body of evidence that there are at least six universal human emotions, expressed by everyone's face identically, regardless of gender, age, or cultural upbringing [my emphasis, URB]. Ekman compiled a Facial Action Coding System (FACS), which is widely used, e.g., by academics and police officers.

Computers now "outperform people in distinguishing social smiles from those triggered by spontaneous joy, and in differentiating between faked pain and genuine pain" (52).

Kaliouby and her colleague Rosalind Picard created the new field in computer science called "affective computing." In the early stages of their work their intentions were highly altruistic. Kaliouby, for example, worked on a project to help autistic patients better interpret human expressions. Her Mind Reader was a program that she hoped would "construct an 'emotional hearing aid' for people with autism. The wearer would carry a small computer, and earpiece, and a camera, to scan people's expressions. In gentle tones, the computer would indicate appropriate behavior: keep talking, or shift topics" (54).

But when the corporate world and the government found out about Mind Reader they swarmed around its inventors with inquiries. "Pepsi was curious if it could use the software to gauge consumer preferences. Bank of America was interested in testing it in A.T.M.s. Toyota wanted to see if it could better understand driver behavior" (56). And so on. And so on. You can bet that the CIA and NSA perked up their ears and antennas. FOX wanted to test all its pilot shows with this software; advertisers all and sundry were fascinated with the idea of using computer software to study a face, and to predict whether that face liked their product. Soon the good intentions and the altruistic impulses of the founder of this software were being stretched out into areas far from altruistic.

Affdex has now been so highly refined that it can "read the nuances of smiles better than most people can" (56). Now there are new projects to upgrade "the detection of furrowed eyebrows." Affdex ran tests on 80,000 brow furrows. Obviously, this computer program now knows infinitely more about brow furrows than anyone on earth.

So what next? The possibilities are rife. Emotion-sensing vending machines and A.T.M.s that would understand when users are in a relaxed mood and susceptible to advertising. Anheuser-Busch has designed a responsive beer bottle, because sports fans at games "wishing to use their beverage containers to express emotions are limited to, for example, raising a bottle to express solidarity with a team" (58).

Next, you suppose, will come the better, new and improved beer bottle with a built-in computer, to study your teeth for cavities and your brain for openings: places where a bit of advertising can intrude. Apple has recently come up with the iWatch, "which can measure heart rate and physical activity, and link these data to your location. The new products complement another line of Apple's research: mood-targeted advertising. . . With the new watch, they are going to know everything about you" (59).

Samsung is quoted as saying, "If we know the emotion of each user we can provide more personalized services" (59). This reminds me of the incessant message over the phone: "your call is being recorded to better serve you," which means, "to better serve us."

Pretty scary stuff, but, you may ask, what does this have to do with Russians or Russian literature? Well, quite a bit, as it so turns out. Take a look at this picture of a Russian face:

[from Barbara Monahan, A Dictionary of Russian Gesture (Hermitage Publications, 1983), p. 27.]

In describing this gesture, Monahan (p.26) cites Edmond Wilson's book, A Window on Russia, and Wilson mentions Anna Karenina's habitual gesture of narrowing her eyes in times of stress. Monahan writes that this gesture indicates, among other things, "I'm concentrating. I'm thinking what I should do next."

The other things (I think) are more important. The gesture, which probably originally came out of a fear of the evil eye, indicates apprehension. The person slitting his/her eyes is engaging in a defensive act, keeping intruding eyes out.

People other than Russians may also use this gesture, but, for example, I think that far fewer Americans do this slit-eyed squint than Russians do (with the possible exception of Clint Eastwood). It comes, largely, out of a thousand years of Russian paranoia.

Russians feel the constant need to protect themselves from hostile eyes. Russian simply do not trust very many people. They wear on their faces a habitual look of sour non-commitment, what Americans see as a frown. It's just not safe to open yourself up too much. In fact, Russians are firmly set against what they call "the American smile," which they consider something superfluous and frivolous. A Russian friend of mine, who has lived in the U.S. for years, walks around with his Russian look on his face, and Americans are constantly asking him, "Sergei, what's wrong?"

So what I'm wondering is this: could the Affdex computer software get anywhere looking at Russian faces? Could it look, say, at Vladimir Putin's face and figure out what he's feeling? Given that Putin wears not only the habitual Russian face mask, but also, on top of that, he wears the mask of the professional spook. So they say, he even sleeps with his spook mask on.

I don't know, but I'm guessing that the Affdex program would scream out for help if it had to deal with the Russian slit-eyed squint. What a shame for all the American mind-reading companies who would like to read Russian minds and make big money in the Russian market!

Labels:

",

" Anheuser-Busch,

"affective computing,

"Anna Karenina,

Affdex,

Affectiva,

Apple iWatch,

Big Brother,

Kaliouby,

Khatchadourian,

Lev Tolstoy,

Paul Ekman,

Picard,

Putin,

Russian faces,

Samsung

Sunday, January 25, 2015

U.R. Bowie, DISAMBIGUATIONS: THREE NOVELLAS ON RUSSIAN THEMES

Here are the first fifteen pages of my forthcoming publication, THREE NOVELLAS ON RUSSIAN THEMES. The first novella features Nikolai Gogol. The first two are set entirely in Russia and have all Russian characters.

THIS BOOK WILL BE AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE ON AMAZON, about Feb. 15, 2015

DISAMBIGUATIONS

Three Novellas on Russian Themes

U.R. Bowie

Эх, русский народец! Не любит умирать своей смертью!

(Oh, these Russian people! No way they want to die a natural

death!)

Русь, куда несешься

ты? Дай ответ! Не дает ответа.

(Rus, whither art thou bound in thy precipitate flight?

Answer me! No answer.)

…Gogol, Dead Souls

CONTENTS

Exhumation

(Эксгумация) 3

The Leningrad Symphony

(Ленинградская Симфония) 37

Disambiguation

(Дисамбигуация) 130

THE

EXHUMATION

1

Троеручица (The Three-Handed)

February, 1842, Moscow

Ekaterina Mikhailovna,

sister of the poet Nikolai Mikhailovich Yazykov, was no Russian beauty, but

there was an aura of beatitude about her. She was only five years old when her

father died. After that she grew up under the sole influence of her pious mother.

She and her mother worshipped together, read through the long list of morning

and evening prayers. They kept the fasts with utter diligence and spent hours

every week bowing down before the icons of Eastern Orthodoxy: the Mother of God

of Vladimir, the Three-Handed Theotokos, the healer St. Panteleimon.

As a small girl Katya

Yazykova would read aloud, drunk with the sound of her own voice, of saints and

martyrs and holy fools, who, despising all that was crass and earthly, embraced

the ethereal, who lived in hovels out in the desert, mortifying their corrupt

flesh with its passions and lusts. At age nine she wept for months on end,

praying and keening, hoping to attain to “the gift of tears.” At ten she went

on an extended fast, eating little but bread and water for forty days. This

feat of zealotry alarmed even her mother, but the little girl said, “No, it’s

all right, Mama. I want to fast my way through to a mantic dream; I hope to

speak with the Holy Mother herself.”

It is not known whether

Katya was ever vouchsafed to see the Mother of God in her dreams, but she

seemed destined for a nunnery, at least until she met the renowned Slavophile

philosopher and poet, Aleksei Khomyakov. After their marriage, in 1836, when

she was nineteen, her life was centered largely on family and children,

although the ideal of the fleshless existence never lost its appeal.

Ekaterina Mikhailovna

became hostess for weekly gatherings of intellectuals and literary figures at

the Khomyakov mansion in Moscow. Those who attended the meetings were

like-minded Slavophiles, firm believers in Eastern Orthodoxy and the holy

mission of Russia. Among them was the comic writer Nikolai Gogol, who had first

met Ekaterina Mikhailovna and her husband through her brother, one of his

closest friends.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

On

those brisk wintry evenings with the pallid yellow of streetlamps flickering on

white frost, Gogol would come to call on the Khomyakovs. The famous author, thirty-three

years old that winter, was short in stature, with a long pointed nose, a

slender build and blond hair. He would smile at his hosts, toss off a few

good-natured remarks, then walk across the drawing room with that peculiar

rapid, herky-jerky gait of his. Standing in a corner, wearing his pale-blue

vest and trousers of a mauve hue, he reminded one guest of the kind of stork

you see in the Ukraine—perched on one leg high up on a roof, with a strangely

pensive demeanor.

In Gogol’s personality

there was something evasive, forced and constrained. He often appeared to be

putting on an act, trying to make people laugh, and no one felt sure of who the

real Gogol was. Early in his career the literary luminaries of the day

(Pushkin, Pletnyov) underestimated him, looked upon him as a figure of fun. The

poet Zhukovsky fondly called him by a silly nickname,“Gogolyok.” Especially in

the last ten years of his life he was all tensed up, nervous to extremes. But

with her, with Ekaterina Mikhailovna, he was almost natural.

Whenever he arrived he

was inevitably drawn to her. Was the attraction sensual in any way? Hardly. In

the whole of his solitary life Gogol was never attracted sensually to any

woman, never had a single affair. What he loved in her was her aura of gentle

piety. They would sit together in a corner, drinking tea, speaking in low

voices. Gogol showed her little of the raucous, hilarious side of himself, the

Gogol who could have people literally crawling on all fours, overcome with

laughter. He never told her the off-color stories he loved to tell, most

certainly never indulged his bent for scatology. With her he relaxed, he gazed

into her lambent grey eyes. Pulled gently into the quiescence that she exuded,

he bathed in its soft glow. Like her, he had been raised in Orthodox

Christianity, and the longer he lived the more his religion took precedence

over everything else.

The conversation

tonight, as almost always, was one-sided. Gogol did the talking, while she

listened to him, responded with her luminous eyes, her soft smile.

“You

know, for years I’ve been planning a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, to pray at

the Sepulchre of Jesus Christ, Our Lord.”

No

answer. Just the smile, the light in her grey eyes. She looked at him, taking

him in without judging him. “Judge not” (Не судите)

were two words she repeated incessantly, silently to herself. Her mother had

taught her to do that. Gogol’s long blond hair fell straight down from the

temples almost to his shoulders, forming parentheses around his gaunt face. His

eyes were small and brown; they would flash occasionally with merriment. His

lips were soft, puffy beneath his clipped mustache, and the nose was bird-like.

Now the mouth was moving again, and she watched it form words.

“I’ll

go there for sure. Some day. Just now I don’t have the energy. My bowels are

giving me fits again. Did I ever tell you that I was once examined by the best

doctors of Paris, and they discovered that my stomach was upside down?”

He

smiled wanly when he told her that, and, as so often with Gogol, she could not

be sure if he was joking or in dead earnest.

“I

think you mentioned that to my brother,” she replied, unsmiling, touching his

wrist with her hand.

Silence.

She was reciting the Jesus Prayer in her mind: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God,

pray for me, a sinner.”

“What

are you thinking?” he asked her.

“Nothing.

I’m listening to what you say. I love your voice.”

That

dreamy expression on her face, the very look of her calmed his soul.

“Maybe

we could all go together—to Jerusalem—with you and your husband, and your brother

Nikolai. Would you like that?”

(Smiling)

“I think it’s a marvelous idea.”

“Who

on earth do I love more than you and Nikolai? No one. Some of my happiest

memories consist of just his presence in my life. The time we’ve spent

traveling together in Europe, or taking the waters. I treasure the memory of

those moments.”

“My

brother loves being with you as well. He’s been quite ill you know, for some

time, but you always cheer him up.”

“I

pray for him. Every day. I know that all will be well, for the Lord is

merciful.”

She

nodded but did not answer. He looked in her eyes again, then recalled a line

from Nikolai Yazykov’s poetry and said it aloud, still gazing in her eyes and

smiling: “Милы

очи ваши ясны” (Mee-loj och-ee vash-oj yas-noj): “Sweet they are, your clear pure

eyes.”

Пуговицы (Buttons)

Early October, 1842, Bad Gastein, Germany

It

was a beautiful sunny day, the air was crisp with early fall. The shade of the

yellow linden leaves was shimmering on a white tablecloth, as they, the two

Nikolais, Gogol and Yazykov, sat at an outdoor café drinking coffee. The

writing had gone well that day, and Gogol was exuberant. Yazykov was afflicted

with spinal muscular atrophy, but the pain in his back went away when Gogol was

full of life. You looked at his face and you felt like laughing.

Gogol’s

blond hair was down to his shoulders, and his brown eyes had that special glint

of gaiety. He wore a gold-rimmed pince-nez on his bird beak. He kept taking it

off and putting it back on.

“You

know what I love?” he asked suddenly, out of the blue.

“What?”

asked Yazykov, smiling.

“I

love vests, all different colors of vests, and I love coats and macaroni, but

most of all I love buttons.”

He

made that last, commonplace word—пуговицы—so

utterly ludicrous in the way he pronounced it that Yazykov burst out laughing.

As

usual, Gogol was making a show of not being in on the joke. He loved to play

out his humor deadpan, and his deadpan look spiced up the game.

“Phoo”

(said Gogol). “You know what I hate?”

(Smiling)

“No, what do you hate?”

Gogol

the actor screwed up his face into a comical grimace, pushing his lips up to

the point where they almost touched the tip of his long nose.

“I

hate high society. I can’t stand the company of ignoramuses!”

(Still

smiling) “I already knew that. You’ve told me time and again.”

(Noticing

the smile and almost dropping the deadpan, letting a smile curve at the corners

of his lips, laughing at himself) “You knew that. Yes. Did you know that what I

need for my work is solitude? Absolute solitude. I should have been a monk!”

Now

they both were laughing, and then Gogol put on a look of feigned annoyance:

“Stop

mocking me, Nikolenka! You can’t deny that there’s no higher calling on earth

than monkdom!”

After

they stopped laughing at that Yazykov spoke up again.

“With

you it all depends on how you’re feeling. If you’re in a melancholy mood and

you say you want to be a monk, well, then I can take you seriously. But if

you’re in a creative mood, the mood you’re in today, then I conjure up an image

of you in a monastery, walking around in a cassock and mumbling prayers, and I

roll on the ground laughing.”

“You’re

right, of course, my friend. Aren’t you always right?”

“You

were reading me those passages from Dead

Souls yesterday, performing the whole thing like an actor, and you came to

the part where Chichikov and Manilov are about to go through a door into the

drawing room, and each of them insists that the other go first. And you were

acting it out, that, “No, please, you go first,” and then, “Oh, no, my dear

sir, I insist, after you.” Sitting there looking at you, I could see the both

of them, first Chichikov, then Manilov, exactly how they looked, even when they

squeezed through the door side by side. You managed to be both of them

simultaneously! When I’m in the presence of something so marvelous, all I can

do is revel in it, and laugh.”

“Bobchinsky

and Dobchinsky,” said Gogol in an absentminded way, thinking of something else.

He took off his pince-nez again, let it dangle from its cord over his

polka-dotted mauve vest.

“Yes, you’re always

right,” he said. “On a day like today I want to live! Listen. Here’s another

joke.”

Nikolai Gogol smiled,

anticipating how funny he would make the story, how he would amuse his friend,

and Nikolai Yazykov smiled as well, at that anticipation.

“A Chukchee Eskimo from

the hinterlands of the Arctic Far East came to visit Moscow. The Chukchee was a

tourist, and he went first of all to see Red Square. He was limping around Red

Square, dragging one foot behind him.”

Gogol stood up from

behind the table and began limping in place as he told it, clacking on the

cobblestones in the high heels of his shoes. Yazykov laughed again.

“He was gimping along,

wearing only one shoe, and a local man, a Muscovite, noticed him.”

Gogol stopped and took

off one high-heeled shoe. He put it down on the tabletop, in a patch of

linden-leaf shade, and continued the limping show, while the gold-rimmed

pince-nez bounced against the bright-yellow polka dots on his vest. Staid

Germans seated at nearby tables looked over in alarm.

“The Muscovite

approached the bedraggled Chukchee.”

Now he was aping the

local man as he walked up, bent nearly double, putting on a silly, ingratiating

face, and Yazykov went off into a different dimension of laughter.

‘Excuse me, Mr.

Chukchee,’ said the Muscovite, ‘but you seem to have lost a shoe.’

‘Oh, no,’ said the

Chukchee.

Gogol was using a

high-pitched Chukchee voice, squinting his eyes to portray an Asian face

steeped in idiocy, and Yazykov was up out of his chair, holding his sides. Then

came the punch line:

‘Oh, no. I found one!’”

Stepping away from

Yazykov, who was grasping the back of his chair, heaving with laugher, Gogol

grabbed a folded umbrella from beside the table and yelled, “Off we go! Time

for a walk!” The Germans at nearby tables went on staring at the spectacle,

disconcerted.

He took back the shoe

from the tabletop, put it under one arm. He stepped out onto the cobblestones,

his blonde hair falling down over his eyes. Holding the umbrella high, like a

drum major’s baton, Gogol marched off down the narrow street, one foot in a

worsted stocking, the other foot shod. Still in the throes of laughter, Yazykov

threw down some coins on the table and raced after him. Bystanders stopped, open-mouthed,

as Nikolai Gogol marched along, totally deadpan. When he reached the fountain

in the center of the square, he suddenly burst out singing a Ukrainian folk song,

then followed that with a swashbuckling dance. He danced on for a few minutes

more, kicking out his legs and swinging the umbrella and the shoe in all

different directions. After that he wrested the other shoe off his foot, threw

both shoes in the air, then turned and danced his barefoot way back to his

friend.

Gogol stopped in front

of Yazykov. He threw the umbrella back over his shoulder. Carefully sticking

the pince-nez in place back on the bridge of his nose, he went into a pose of

frozen startled bewilderment, mimicking the mayor in the final, dumb scene of

his play, The Inspector General.

Then, squeezing his long slender proboscis, pinching it with a forefinger and

thumb, he put on a cross-eyed face and improvised in a nasal voice on a line

from his famous story, “The Nose”:

“No, my dear sir. You

are mistaken. By no means and in no way am I your very own nose. I, my good

man, am my very own man!”

Очей Милых Нету (Dear Eyes Gone)

January, 1852, Moscow

She

died young, of typhoid fever, on January 26, 1852. After the requiem service (panikhida) that he himself had arranged

for her, in the private chapel of Count A.P. Tolstoy, Nikolai Vasilievich

Gogol, his whole body shaking with sobs, stood in the arms of her husband,

Khomyakov.

Aleksei

Khomyakov pushed back the mop of brown hair from his brow, in that

characteristic gesture of his. He knew he had to be strong; he saw the state

that Gogol was in.

“How

can it be, Aleksei Stepanovich? How can it be that she’s gone?”

“God

is merciful, Nikolai Vasilievich. Somehow we will learn to bear this.”

Gogol

no longer wore the gold-rimmed pince-nez. He had on a black frock coat with

long tails and little mother-of-pearl buttons. He had lost a lot of weight and

his clothing hung loosely on his frail body.

“Yes. God always takes

the best. No human thought can imagine even a hundredth part of the infinite

love that God has for man! And death. Life would not be so precious and

beautiful, if not for death.”

“Thirty-five

years old, Nikolai Vasilievich. She was only thirty-five. What will I do with

the children?”

“Her

eyes, Aleksei Stepanovich. How can it be that those grey eyes are gone? I can’t

bear it, my friend. When Nikolenka died in 1846, I felt as if I were left

missing a limb. And now this. No, this is worse. This means the end for me. I’m

finished.”

“It’s

a terrible blow, Nikolai Vasilievich, but we must go on.”

“I

pray for her every day. I pray on into the night. I fast and pray.”

“Try

to get a grip on yourself, Nikolai Vasilievich.”

“I

fear nothing now. The Lord has a grip on me.”

“You

must go back to your writings.”

“It’s

too late. God in His wisdom has taken from me the ability to create. I long

have tortured myself, forced myself to write, but all to no avail. I will never

finish the rest of Dead Souls. My soul

is dead to the written word. Only prayer can help me.”

“My

friend, this severe regimen of fasting, it’s not good for you. She would have

told you so herself. You must eat. And sleep.”

No

reply. He did not want to eat, nor did he want to sleep. He wanted to die.

“I

can still see her riding sidesaddle on that horse. Remember, Nikolai

Vasilievich? All decked out, wearing garlands in their hair, festoons of

flowers, she and Lise Chertkova, they came riding up to your name day party,

laughing at the open mouths of the guests as they made that grand entrance on

horseback. It was at the Pogodin house, we were all out in the gardens. They

had nightingales in cages. The Aksakovs were there, the Elagins, Nashchokin,

Professor Botkin. Who else? It was May 9, but which year? 1841? 1842? Right

before you left to return to Rome.”

Gogol

was barely listening.

“It’s

too late, and now she’s gone. I can’t bear such a loss.”

“Then

you made a punch for all the guests, out in the arbor. You were lighting a

mixture of rum and champagne, and you compared that blue flame to the uniform

of the secret police, and you said that flame represented the chief gendarme,

Count Benkendorf, who would now proceed to occupy the stomachs of all the

guests, where he would restore order. Do you recall that joke, Nikolai

Vasilievich?”

“I went to the Holy

Land, hoping to find peace of mind, desperate to learn what the Lord wanted of

me. I prayed beside the tomb of the Son of God and felt nothing! What a shame

that she didn’t come with me. It might have been different. What did I bring

back? Somewhere in Samaria I plucked a wild flower; somewhere in Galilee

another. Nothing else. It’s hopeless.”

“Nothing

is hopeless while we still have life.”

“Her

eyes are gone. The way she would look at me. That just can’t be. ‘Sweet they

are, your clear pure eyes.’”

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Less

than a month later, refusing to eat, barely sleeping, praying incessantly,

Nikolai Gogol burned the pages of his manuscript for the second part of Dead Souls, took to his bed, and died of

exhaustion, inanition, emaciation. He was not quite forty-three years old.

Gogol was buried at the Danilov Monastery cemetery in Moscow, not far from the

gravesite of Ekaterina Mikhailovna Khomyakova.

2

Накануне (On the Eve)

It

was eight p.m. on June 25, 1931, and the renowned bibliophile, Professor

Vladimir Germanovich Lidin, was relaxing at his spacious apartment on Semashko

Street in Moscow. He was rearranging the books on his shelves, placing Fyodor

Dostoevsky up a shelf higher than Lev Tolstoy, then moving him back to a shelf

lower.

Lidin,

a fastidious middle-aged bachelor with a balding head, wearing a red dressing

gown imported from Persia, smiled as he worked, losing himself in conjectures

about the only topic on earth that enthralled him: Russian literature. Now, if

Tolstoy and Dostoevsky had met on that evening in 1878, when they both were in

the lecture hall for Solovyov’s talk. . . had they met, what would they have

said to each other? Or this: had Pushkin not been killed in a duel at a young

age, would he, rather than Tolstoevsky, have turned out to be the great voice

of the Russian realist novel? Or perhaps Lermontov? What if Gogol had talked

some sense into his refractory head, young Lermontov’s, on the one time they

met in 1840?

That’s when the phone

rang.

--Hello.

--Is

that you, Vladik?

--One

and the same (said Lidin, who put on a face of light irony for the world at

large).

--

It’s Petya. Big news. Are you busy tomorrow?

--I

don’t know, Petya. Depends on how big the news is.

Pyotr

Borisovich Ertel (Petya), a casual friend, who held a sinecure at the

Historical Museum, was a wiry man of thirty-four, with a swirl of curly black

hair that quavered and danced on his head. He spoke with a perpetual air of

glib ingratiation, as if always hoping that his words would please, while

fearing they would not.

--Tomorrow they’re

doing an exhumation. They’re disinterring Nikolai Gogol at the Danilov

Monastery!

--That’s

big news indeed. Why are they digging him up?

--They’re

closing down the cemetery at Danilov, making the monastery into a home for

wayward boys. Anyone who’s anyone gets moved to Novodevichy. Anyone who’s not

just loses his tombstone, but stays right there underground and goes on

mouldering.

--If

I were there, Petya (joked witty Vladik), I’d prefer to be one of the ones

who’s nobody. That way they’d leave me alone.

--Yes,

if you want to remain un-exhumed, being a nobody has its advantages.

--Who

are the other honorees, i.e., the ones being dug up?

--Don’t

know yet. I guess we’ll find out tomorrow.

--Sounds

interesting. What time does this macabre little party begin, Petya?

--Try

to get there early in the morning; that way you won’t miss anything.

After

hanging up the phone, Professor Lidin sat motionless for a few moments. A

member of the Soviet intelligentsia and, consequently, a muser on issues of

deep philosophical import, Lidin was caught up in flights of fancy.

So

Nikolai Vasilievich died in 1852, and now they’re digging him up. If I were to

think illegal thoughts, which, in the new age of the rationalistic Soviet man,

I, of course, will not dare to think, but for purposes, merely, of discussion,

let’s say I could think them. . . . Yes. So when Gogol died he had a soul (it

was so presumed), and, according to then widely accepted religious beliefs, at

the time of his death the soul was separated from the body and ascended into

Heaven, which, of course, does not exist. Gogol wrote a whole novel about

souls, living and dead, and, at least in the context of that book, he seemed

convinced that almost every soul on earth was more dead than living, that is

(not to put too fine a point on it), corrupted in a moral sense.

Then

later, alarmed at the iffy state of his own soul, fearing that it might likely

even fall into the category of dead, he went into a religious frenzy. He had

hopes of reviving his dead soul, or at least making it qualify for redemption

at the time of the “Last Judgment.” He prayed zealously, for hours on end, he

fasted to the point of excruciation, and he, of course, wrote on and on, obsessively,

hoping to complete the second and third volumes of Dead Souls. By the very act of completing the novel, so he reasoned

in his megalomania, he would discover the meaning of life and save the world.

But he never could complete the book, and he fell into despair and burned the

manuscript (see Ilya Repin’s famous painting of the burning), and then he

starved himself to death.

At

any rate, when they dig him up tomorrow, what will they find? A skeleton in a

frock coat—that’s the most likely thing—but not a soul, not even a dead soul.

And what if the body lies un-decayed? In the Russian Orthodox Church (back when

it still existed) if you dug up a body and it was uncorrupted that was a sign

of sainthood. Yet, then again, these thoughts are all atavistic remnants of a

former time. In the new Age of Socialism we have pitched all such religious and

superstitious conjectures off the ship of modernity, which steams ever onward

toward Utopia. We are aware, are we not, that flesh we are, and flesh alone,

and ‘soul’ is simply another word for something made of flesh?

Yes.

And what about ancient folkloric proscriptions worldwide against tampering with

dead bodies in graves? Well, if there are no souls, there are, consequently, no

ghosts, and, therefore, we need have no qualms about disinterring dead bodies

and, in the interest of scientific progress, having a look at what’s left of

the remains. In our New Soviet time feeling queasy about such things places one

in the camp of the reactionaries. Yes.

Friday, January 23, 2015

"Anna Karenina" WHEN EYES AND SMILES SAY IT ALL

(15) Eyes and Smiles

We've seen in our discussion that a perverse mushroom cannot distract Kitty in her love for Lyovin (see previous posting, "Love and Mushrooms"). Eyes and smiles say it all. And this brings us to the famous chalk-writing scene of the marriage proposal (Part Four, Ch. 13):

"She had completely guessed and expressed his badly expressed idea. Lyovin smiled joyfully. He was struck by this transition from the confused, verbose discussion with Pestsov and his brother to this laconic, clear, almost wordless communication of the most complex ideas.

Scherbatsky moved away from them, and Kitty, going up to a card table, sat down, and, picking up the chalk, began drawing spirals over the new green cloth.

They began again on the subject that had been started at dinner--the liberty and occupations of women. Lyovin was of the opinion of Darya Aleksandrovna [Dolly], that a girl who did not marry should find a woman's duties in a family. He supported this view by the fact that no family can get on without women to help;that in every family, poor or rich, there are and must be nurses, either relations or hired.

"No," said Kitty, blushing, but looking at him all the more boldly, with her truthful eyes; "a girl may be in such a situation that she cannot live in the family without humiliation, while she herself . . ."

At the hint he understood her.

"Oh, yes," he said. "Yes, yes, yes--you're right; you're right!"

And he saw that all that Pestsov had been maintaining at dinner about the freedom of woman, simply from getting a glimpse of the terror of an old maid's existence and its humiliation in Kitty's heart; and loving her, he felt that terror and humiliation, and at once gave up his arguments.

A silence followed. She was still drawing with the chalk on the table. Her eyes were shining with a soft light. Under the influence of her mood he felt in all his being a continually growing tension of happiness.

"Ah!" I've scribbled all over the table," she said, and laying down the chalk, she made a movement as though to get up.

"What! Shall I be left alone--without her?" he thought with horror, and he took the chalk. "Wait a minute," he said, sitting down to the table. "I've long wanted to ask you one thing."

He looked straight into her caressing, though frightened eyes.

"Please, ask it."

"Here," he said; and he wrote the initial letters w, y, t, m, i, c, n, b, d, t, m, n, o, t. These letters meant, "When you told me it could never be, did that mean never, or then?" There seemed no likelihood that she could make out this complicated sentence; but he looked at her as though his life depended on her understanding the words. She glanced at him seriously, then leaned her puckered brow on her hands and began to read. Once or twice she stole a look at him, as though asking him, "Is it what I think?"

"I understand," she said, flushing a little.

"What is this word?" he said, pointing to the n that stood for never.

"It means never," she said, "but that's not true!"

He quickly rubbed out what he had written, gave her the chalk, and stood up. She wrote t, i, c, n, a, d.

Dolly was completely relieved of the depression caused by her conversation with Aleksey Aleksandrovich when she caught sight of the two figures: Kitty with the chalk in her hand, with a shy and happy smile looking up at Lyovin, and his handsome figure, bending over the table with glowing eyes fastened one minute on the table and the next on her. He was suddenly radiant: he had understood it meant, "Then I could not answer differently."

He glanced at her questioningly, timidly.

"Only then?"

"Yes," her smile answered.

"And n . . . and now?" he asked.

"Well, read this. I'll tell you what I would like--would like so much." She wrote the initial letters i, y, c, f, a, f, w, h. This meant, "If you could forget and forgive what happened."

He snatched the chalk with nervous and trembling fingers, and breaking it, wrote the initial letters of the following phrase, "I have nothing to forget and forgive; I have never ceased to love you."

She glanced at him with a smile that did not waver.

"I understand," she said in a whisper (p. 416-419).

This scene goes on for some time longer, and at the end of the scene "everything had been said [without words]. It had been said that she loved him, and that she would tell her father and mother that he would come tomorrow morning."

Hard to believe that two souls could be so closely attuned? When I was teaching at Miami University I used to try this experiment. I would tell the students that the subject was romantic love and write these letters on the blackboard: i, l, y, m, t, l, i. A lot of the students would immediately figure it out: "I love you more than life itself." But then, I would say, what if the speaker were a recovering alcoholic and his estranged lover was called Inez? "I loathe you more than liquor, Inez." Next I would write, i, i, w, t, t, y, t, t, w, s, i, h, w, w, y, b, m? Nobody got that: "If I were to tell you that this whole scene is hogwash, would you believe me?"

In a way it IS hogwash; at least it is difficult to believe that the two characters could pull off this feat of mind-reading. It is always dangerous for an artist to use scenes directly from his own life's experience. Why? Because creative fiction is supposed to be believable, and life is often far from believable.

Tolstoy took this chalk-writing episode directly from his own life: his proposal to his wife. Or did he? In his biography of Tolstoy, A.N. Wilson describes this scene from the lives of Tolstoy and his wife-to-be Sonya. Then Wilson goes on to say that it was probably jointly invented by Tolstoy and Sonya and then believed by both of them. It became, if Wilson is correct, one of those family folklore things that get retold over and over, to the point where everyone is convinced that it had to have happened just like that (see A.N. Wilson, Tolstoy, p. 192-94). But who knows?

Thursday, January 22, 2015

JOHN UPDIKE ON: Charles D'Ambrosio ("Up North"), Natalie Portman, Julia Roberts ("Closer"), Woody Allen ("Match Point"), literary fiction, fluency in Russian, Philip Roth, Zuckerman, Zuckerman's prostate gland, etc.

Wednesday, January 21, 2015

"Steal Like an Artist" TOLSTOY TO CHEKHOV TO BUNIN TO NABOKOV

In his Youtube video (see below for link) Austin Kleon tells us something all artists have known since time out of mind: that art is not totally original, that it comes out of previous art.

"Nothing is original," says Kleon, and all artists are "creative kleptomaniacs."

If you want to become a creative writer, read creative literature. If you want to become a great creative writer read GREAT writers. Then write. Some twenty years later, if you are still reading great writers and still practicing your craft every day, you will become, maybe not a great, but probably at least a GOOD writer. This does not mean that you have plagiarized from the great artists. No, you have taken the creative coals from their fires and you have blown on those coals, and you have built your own fires upon those coals and your own breath.

Then again, if you are a feminist you may not want to read the great male writers, many of whom are, let's face it, quite often misogynists. So no problem: read Virginia Woolf, Rebecca West, Flannery O'Connor. But don't make the mistake of thinking that, e.g., To Kill a Mockingbird, is a great novel. As Flannery once said, "this is a children's book."

As for Russian literature, examples of creative artists as thieves are easy to find. Tolstoy wrote Anna Karenina. Chekhov read and loved AK, and he wrote lots and lots of stories with heroines named Anna. Those stories were, while original, the creative offspring of Tolsoy's AK. One of them, "The Lady with the Dog," is one of Chekhov's most well-known stories. Bunin also loved AK, but he also read "The Lady with the Dog." His story "Sunstroke" comes, largely but not entirely, out of his reading of AK and "The Lady with the Dog." Nabokov read AK, loved it, but he also read Chekhov and Bunin. His story "Khvat," (in English translation, "A Dashing Fellow") is a brutal parody on Bunin's "Sunstroke." But this Nabokov story would also not have been written without the tacit participation of Tolstoy and Chekhov.

So it goes. At least so it goes in part. Given that any writer has read many many different things and has had a whole plethora of personal experiences to draw on, what finally comes out on the page cannot be ascribed totally to that writer's reading of only Tolstoy, or only Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Bunin.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oww7oB9rjgw

Monday, January 19, 2015

BOOK REVIEW: MAXIM SHRAYER, "Bunin and Nabokov"

BOOK REVIEW

Maksim D. Shraer ( Maxim Shrayer). Bunin i Nabokov: istorija sopernichestva

[Bunin and Nabokov: The History of a

Rivalry] (2-oe izdanie). Moskva: ANF, 2015. Index of names. 219 pp. Cloth.

Available on Amazon and at www.biblio-globus.us.

“When Bunin and Nabokov are together,

looking at each other, it’s like two movie cameras are running.”

…Mark Aldanov, cited on p. 95

[All translations from the Russian in

this review are mine—URB]

Professor

Shrayer has been working his way toward the publication of this fascinating book

since his days in graduate school at Yale. His dissertation (1995) is titled,

“The Poetics of Vladimir Nabokov’s Short Stories, with Reference to Anton Chekhov

and Ivan Bunin.” For a complete listing of everything he has published on Bunin

and Nabokov since then, see note 22 (185). It is certainly an impressive list.

Now, having worked some twenty years on the two writers and their relationship—studying

their literary works, reading their letters and diaries in archives (with the

help of the redoubtable Richard Davies at the Leeds Russian Archive),

consulting any and all commentary on their works and lives—Shrayer has

ferretted out practically everything extant in regard to Bunin and Nabokov. The

result is this compact book, laden with interesting facts and even highly

entertaining.

The two authors tiptoed around each

other for years, danced together and apart (mostly apart), sparred in personal

meetings and on paper. Nabokov-Sirin used,

or attempted to use Bunin at various times in furtherance of personal literary or

life’s goals. Bunin had no need to use the younger writer in such ways, but he

was acutely aware of Nabokov’s growing reputation in the thirties. As the story

begins Bunin, thirty years older than Nabokov, is already the most famous

Russian writer of the emigration, and young Nabokov is in awe of him. The

cajolery and flattery begins with Nabokov’s father, the famous jurist, politician

and publicist V.D. Nabokov (1869-1922). Bunin knew him personally; they had met

on several occasions.

On Dec. 12, 1920, the elder Nabokov

writes a long and obsequious letter to the old master, thanking him profusely

for the enormous artistic delight that Bunin has delivered to him and to all

readers of the journal “Rul’. After

waxing eloquent on Bunin’s artistic glory, the politician Nabokov finally gets

around to his real reason for writing: “If you have come across my son’s verses

in ‘Rul’ (signed Cantab.), please let

me know your opinion of them”(30). The elder Nabokov goes on buttering up the

master (31-33), and then the young writer Nabokov himself, still a student at

Cambridge, sends his own first letters, which, given the mature author’s pose

of arrogant superciliousness, are shocking for their self-abnegating servility (33-35).

In the second of these letters Nabokov

includes a poem dedicated to Bunin. In the first he thanks Bunin for writing

about “my timid creative works” (o moem robkom tvorchestve), and concludes by practically

asking Bunin to be a father figure to him: “Slovom, khochu ja vam skazat’, kak

beskonechno uteshaet menja soznan’e, chto est’ k komu obratit’sja v eti dni

velikoj sirosti (In a word, I’d like to tell you how infinitely I am consoled

by knowing I have someone to turn to in these days of great bereavement”—34). Nabokov’s

father was murdered on Mar. 28, 1922. The bereavement in this letter apparently

alludes to the recent loss of the homeland, but there is also here a remarkable

premonition. Almost as if Nabokov anticipated his father’s death and his

personal bereavement (sirost’—“orphanhood”),

which came a year after this letter was written.

A big issue right from the start is

this: in the authors’ personal relations, in their letters to one another, in

the inscriptions they wrote each other in the frontispieces of gifted books,

how can you distinguish sincerity from insincerity? One fact shines through the

posturing and the fakery: Nabokov was consistent over the course of a lifetime

in his love for Bunin’s poetry. In a letter of May 11, 1929, he mentions that

while still a child he had already memorized a lot of the verses, and a week later

he “complains” that Bunin in a recent publication of his collected poems had

changed some of his favorite lines. He informs Bunin that he has identified the

butterfly in one of the poems (37-38).

In a reading at a gathering in Berlin,

in Dec.,1933, the two writers finally met, after years of corresponding by mail

(84). At this occasion Nabokov-Sirin made a speech about Bunin as a poet and

declaimed some of his favorite Bunin verses. Much later, in requesting that

Nabokov read in his honor at a festive occasion in New York (in 1951), Bunin

may have recalled that reading in Berlin and anticipated Nabokov’s again

declaiming his poetry (168). An interesting footnote: in 1945 Bunin declared that

Nabokov’s poetry was better than his prose (43).

It cannot be overemphasized how much young

Nabokov’s appreciation of his verse must have meant to Bunin, whose poetry was

widely scorned as old-fashioned, and had been so scorned by the modernist writers

he hated even before his emigration. One of my professors from graduate school,

the poet Yurij Pavlovich Ivask, who knew Bunin personally in France, held his

prose in high esteem, but spoke with mockery of his verse. Ivask’s attitude

expressed that of the majority. In consistently praising Bunin’s poetry over

his lifetime, Vladimir Nabokov was very much in the minority.

As for Bunin’s prose, Nabokov blew hot

and cold over the course of his lifetime. In a letter to his wife, e.g. (July

16, 1926), he once expressed a high opinion of what was to become one of Bunin’s

most well-known stories, “Sunstroke” (“Solnechnyj

udar,”—“velikolepnyj rasskaz Bunina” (44), but not long after that, in the

early thirties, he wrote a brutal parody of the story:“Khvat”—“A Dashing Fellow” in English translation. [My opinion, URB;

Prof. Shrayer does not mention this story]. Later he included “The Gentleman

from San Francisco,” to this day Bunin’s most well-known work in the West, in a

list of recommended reading for his students at Harvard (173).

Given Nabokov’s love for Bunin’s poetry,

Prof. Shrayer raises the question of to what extent the beloved verses

influenced the tonality and style of Nabokov’s creative writing. A good

question, but an even better question is to what extent Bunin’s prose style was

instrumental in Nabokov’s development. Nabokov spent a lifetime denying that

the prose had any influence on him, but time and again Shrayer cites comments

of critics to the contrary. He writes (76) that “above all, Nabokov learned

from Bunin the art of intonation and rhythm in prose.” I say amen to that. Gleb

Struve also had it exactly right in what he wrote in 1936: “It’s hard to find

any ancestors for Sirin in Russian literature. As a stylist he learned a thing

or two from Bunin, but it’s hard to imagine any two writers more different in

their spirit and essence” (93). Maja Kaganskaja is also perspicacious in

remarking (134) that Nabokov took Bunin’s style and used it in the service of

an anti-Bunin poetics.

In discussing the congruence of prose

styles, Prof. Shrayer (76) compares a passage from “The Gentleman from San

Francisco” with a passage from Nabokov’s “Pil’gram” (in translation “The

Aurelian, 1930). You could do this with any number of prose works. Some of

Nabokov-Sirin’s earliest stories so resemble Bunin that they could almost have

been written by him. Take, e.g., “The Word,” published in 1923, and translated

into English by Dmitri Nabokov long after his father’s death (The New Yorker, Dec. 26, 2005 and Jan.

2, 2006). Here we have the almost plotless story line so favored by Bunin in

his early years, the long intricate sentences, the lush, over-lavish style, the

Romantic extravagance:

“Wings, wings, wings [of angels]! How

can I describe their convolutions and their tints? They were all-powerful and

soft—tawny, purple, deep blue, velvety black, with fiery dust on the rounded

tips of their bowed feathers. Like precipitous clouds they stood, imperiously

poised above the angels’ luminous shoulders; now and then and angel, in a kind

of marvelous transport, as if unable to restrain his bliss, suddenly, for a

single instant, unfurled his winged beauty, and it was like a burst of

sunlight, like the sparkling of millions of eyes” (New

Yorker, p. 76).

“A kind of marvelous transport.” Yes,

but a story overloaded with such passages may make for a bit too much

transport. In reading this, one is reminded of the way Gorky and Chekhov

cautioned Bunin to stop overloading his sentences and paragraphs, of how Yury

Olesha found too much sparkling lavish imagery in “The Gentleman from San Francisco.”

I wonder if “The Word,” almost fustian in its Romantic loftiness, would have

even been published, had Nabokov still been alive in 2005. In his preface to the

collected stories, Dmitri Nabokov gives half a page to “The Word,” mentioning

its “ingenuous rapture,” but, of course, saying not one word about Bunin. See The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov, N.Y.,

1995, p.xvii. The story is notably absent in the “Bottom of the Barrel” list in

the front matter (Nabokov’s listing of the last of the early Russian-language

stories to be translated into English).

You may reply, “All right, Bunin’s

influence was there early on, but Nabokov soon left behind such hyper-lyrical,

exalted prose. He quickly transcended his dependence on the old man.” You’re

right. He did of course go off in a completely different direction; his

metaphysics and Bunin’s have nothing in common, and the modernist movement in

literature is a more important influence on him in his mature years.

But take a percipient reader of

Nabokov’s best stuff in English. A man

who considers Nabokov the best American writer of his time. One who has never

read Bunin. Send him “The Gentleman from San Francisco” to read. In 2006 I sent

John Updike a copy of my Bunin translations (Night of Denial, Northwestern University Press, 2006). Here is a

quotation from a post card he wrote me that year: (see above, top of this posting).

“I had never read a word by Bunin and

read instantly the two stories you urged and then ‘The Gentleman from SF,’ in

its full-throated style of translation. . . . . He is strikingly like Nabokov

in his hyper-realism, in his insistence on wringing the last drop of

descriptive elegance from his prose. . . .”

So there you have it. It is as if Bunin were

a writer obviously influenced by Vladimir Nabokov, who was fifteen years old

when “The Gentleman from San Francisco” was published. Throughout the whole of

his life Nabokov never once acknowledged his stylistic debt to Bunin’s prose

style. In his Russian-language memoir, Drugie

berega, he dismisses Bunin’s “parchovaja proza, (brocaded prose)” and

writes a parody of it (179-80, 175). This strikes me as one of Nabokov’s

diversionary maneuvers, something like the way he implicitly denied his affair

with Irina Guadanini in letters to his wife by expressly mentioning Guadanini and telling Vera (in English) “don’t

you dare be jealous” (109—letter of Feb. 15, 1937). There was no love affair,

but oh yes there was; there is no “brocaded prose” in Nabokov’s style, but oh

yes, there is.

Nabokov’s almost total rejection of

Bunin as a prose writer came late in his life, after his emigration to the U.S.

It was certainly influenced by years of accumulated personal animosity between

him and the old master. Prof. Shrayer takes Nabokov’s final verdict on Bunin

(“a prose writer whom I rank below Turgenev”) as the title of his last chapter.

He is especially good at detailing how the two came to despise each other over

twenty years of émigré life in Europe. Of course, one could certainly have

predicted the souring of the relationship, given the hyper-developed ego of

most literary artists. Shrayer never says so, but what Bunin and Nabokov have

most in common is their excessive pride and the almost megalomaniac nursing of the

personal ego.

Of course, Nabokov is notorious for his

judgments on some of his compatriots. His rankings of Russian writers for his

students, as Prof. Shrayer acknowledges (169) cannot be taken seriously. His

opinion of Gogol took radical dips and swoops at various points in his life,

but he wrote a book about the great man that comes out, primarily, as a

burlesque of Gogol and an exaltation of himself. As for Dostoevsky, despite

Nabokov’s vehement condemnation of him, his constant attempts to toss him

overboard, off the ship of Russian Literature (Bunin shared his opinion of

Dostoevsky), the history of Russian Literature, when it makes its lists, will always rank Dostoevsky

in the Top Five, above Nabokov.

As for Bunin’s prose works, few would

argue that “The Gentleman from San Francisco” does not belong in the pantheon

of great Russian literature. Or take Drydale

(Sukhodol), the best novella Bunin wrote and one of the best any Russian has

written. Then there is “Light Breathing,” generally acknowledged as Bunin’s

best short story. Nabokov once mentioned that this was his favorite Bunin

story. The list could go on.

You can follow the change in the

relationship of Bunin and Nabokov by reading successive inscriptions written by

Nabokov in the books he published and gifted to Bunin. The inscriptions are at

first meek, ingratiating. The novel Mashen’ka:

“Most deeply respected and dear Ivan Alekseevich, with joy and terror I send

you my first book. I beg of you, do not judge me too harshly. With all my soul yours.

V. Nabokov (44-45).” The collection of stories and poems, Vozvrashchenie Chorba: “To Ivan Bunin. To the great master from a

sedulous disciple. V. Nabokov” (49).

By the early to mid-thirties Nabokov

had, in his fame and renown in émigré circles, overtaken Bunin. He was widely

considered the best writer of the emigration. Meanwhile, he came across Bunin

frequently in émigré literary circles and did not much like him. By 1936, when

he sent Bunin his novel Otchajanie

(Despair) his inscription reads as if written by one who cannot think of a

single genuine thing to say: “Dear Ivan Alekseevich, It was really, really nice

seeing you in Paris [one too many “reallys” here, struggling to be sincere,

failing]. But there remain thousands [read “zero”] of things that I have not

expressed to you, and now all of that won’t fit into this inscription in a

book. At any rate, I send you heartfelt [not really] greetings!” [exclamation

point, striving to be genuinely exclamatory, failing] (107).

In 1938, sending Bunin Invitation to a Beheading, a novel that

he surely knew would enrage the old man, Nabokov wrote a short and stereotyped

inscription: “To Dear Ivan Alekseevich Bunin, with the sincerest [s samim luchshim—literally, “with the

very best”] of greetings from the author” (121). For Bunin’s (enraged) reaction

to the novel, see p. 88. In reading the later, most mature, of Nabokov-Sirin’s

Russian-language works, Bunin’s rage knew no bounds. See, e.g., p. 136, where

Bunin tells of re-reading “the bizarre and lewd Gift, swearing (rugajas’

materno) as I read,” and calls one of Nabokov’s best stories, “Spring in

Fialta,” “nothing but banal vulgarity (odna

poshlost’).”

It is no surprise that Bunin, a man

whole favorite nephew once nicknamed “Sudorozhnyj” (The Convulsive One), would

not sit idly by and watch his literary fame be overshadowed. But despite his

aggravation with Nabokov-Sirin, which intensified as Nabokov’s star rose ever

higher, Bunin could be remarkably generous in his praise of his younger

colleague—although he delivered that praise through gritted teeth. Examples are

rife throughout Shrayer’s book. Here are a few:

“He has discovered a whole new world,

and for this we must be grateful to him” (56). “He’s a monster, but what a

writer” (102). When they met later Nabokov asked Bunin, “What are you doing

calling me a monster?” (111). Other of Bunin’s terms of endearment: he’s a

“joker in a cheap sideshow” (shut

balagannyj), he’s “a slapdash cabdriver outside a midnight dive” (likhach vozle nochnogo kabaka) (144),”

he’s “a jackass buffoon” (shut gorokhovyj)

(144), “a red-headed circus clown” (143). The thing about the circus clown here

is in reference to the hated Aleksandr Blok, but Bunin sometimes saved time and

energy by using the same invective for Blok and Nabokov (note, once again, the

grudging admiration): “There you have probably the most adroit writer in all of

the boundless realm of Russian literature, and he’s a red-headed circus clown.

But, sinner that I am, I love talent, even in clowns” (this quotation is not in

Shrayer’s book; it is cited in Aleksandr Bakhrakh, Bunin v khalate, 1979, p. 110).

At one point, before they had met, Bunin

even applied one of his favorite theories on “degeneracy” to Nabokov: “’What

does he look like?’ asked Jan [Bunin]. He doesn’t resemble his father, who was

a nobleman (barin). With him you

sense a definite degeneracy” (58—from the diary of Vera Bunina, Jan., 1931). On

Bunin’s interest in degeneracy, see Ivan Bunin, Night of Denial (translation, critical afterword and notes by R.

Bowie) Northwestern University Press, 2006, p. 579-80.

As is obvious by some of the quotes

above, by the mid-thirties the antagonism between the two writers had become

personal. In letters to his wife Nabokov emphasized how Bunin’s very appearance

was repulsive. “Bunin is turning out to be nothing but an old vulgarian” (110).

“He is “gruesome, pitiful, bags under his eyes, the neck of a tortoise,

constantly tipsy” (111). Bunin in the mid to late thirties had become truly

pitiful, after his lover and protégé Galina Kuznetsova left him. He never

recovered from this loss (90-91). But are the pitiful ever pitied? Seldom. In

English the words “pitiful” and “pathetic” have secondary, pejorative meanings.

Bunin did not include Nabokov among

those he excoriated in his remarkably acerbic and bilious Reminiscences (1950), but Nabokov made mention of Bunin, both in

his Russian memoirs, Drugie berega,

and in his English-language Conclusive

Evidence and Speak, Memory. In a

letter to his wife Vera (sent Jan. 30, 1936), he describes a meeting with Bunin

in a Paris restaurant (95-96), and he elaborates on that meeting (rather, he embellishes

it) in the memoirs. Prof. Shrayer cites this passage in all its variants

(95-100). Here is how it goes in Speak,

Memory:

Another

independent writer was Ivan Bunin. I had always preferred his little-known

verse to his celebrated prose. . . . At the time I found him tremendously

perturbed by the personal problem of aging. The first thing he said to me was

to remark with satisfaction that his posture was better than mine, despite his

being some thirty years older. He was basking in the Nobel prize he had just

received [actually three years previous to the meeting here described—the

basking was already over, URB] and invited me to some kind of expensive and

fashionable eating place in Paris for a heart-to-heart talk. Unfortunately, I

happen to have a morbid dislike for restaurants and cafes, especially Parisian

ones—I detest crowds, harried waiters, Bohemians, vermouth concoctions, coffee,

zakuski, floor shows and so forth. I

like to eat and drink in a recumbent position (preferably on a couch) and in

silence. Heart-to-heart talks, confessions in the Dostoevskian manner, are also

not in my line. Bunin, a spry old gentleman, with a rich and unchaste

vocabulary, was puzzled by my irresponsiveness to the hazel grouse of which I

had had enough in my childhood and exasperated by my refusal to discuss

eschatological matters. Toward the end of the meal we were utterly bored with

each other. “You will die in dreadful pain and complete isolation,” remarked

Bunin bitterly as we went toward the cloakroom. An attractive, frail-looking

girl took the check for our heavy overcoats and presently fell with them in her

embrace upon the low counter. I wanted to help Bunin into his raglan but he

stopped me with a proud gesture of his open hand. Still struggling

perfunctorily—he was now trying to

help me—we emerged into the pallid

bleakness of a Paris winter day. My companion was about to button his collar

when a look of surprise and distress twisted his handsome features. Gingerly

opening his overcoat, he began tugging at something under his armpit. I came to

his assistance and together we finally dragged out of his sleeve my long woolen

scarf which the girl had stuffed into the wrong coat. The thing came out inch

by inch; it was like unwrapping a mummy and we kept slowly revolving around

each other in the process, to the ribald amusement of three sidewalk whores.

Then, when the operation was over, we walked on without a word to a street corner

where we shook hands and separated (Speak,

Memory, revised ed., 1966, p.285-86).

Can we ever really trust the

reminiscences of a creative writer of fiction? A creative writer loves to make

as much creatively as possible out of a remembered incident. One interested in

comparing variants of the story related here, both in three different memoirs

and a personal letter, may consult Prof. Shrayer’s book (95-100). Late in his

life Bunin, exasperated by this tale, denied that it had ever happened, even

denied that he had ever been in a restaurant with Nabokov (170-72).

Of course, even were the episode related

with exactitude, Nabokov’s arch, condescending and supercilious tone here would

have driven Bunin beside himself. But what really happened? Did Nabokov make up