The Bronze Horseman, Detail: Head of Peter the Great

Book Review Article

Petrie Harbouri, The Brothers Carburi. London:

Bloomsbury Publishing, 2001, paperback 2002, 311 pp.

Three Brothers

Giovanni Battista Carburi (1722-1804)

Marino Carburi (1729-1782)

Marco Carburi (1731-1808)

This novel tells the story of three brothers who lived in

the eighteenth century. Born in the Greek Ionian Islands, which were at the

time in possession of the Republic of Venice, “none of the brothers thought of

himself as Greek.” The language they most speak and think in is Italian,

although many other languages come into play: Greek, Latin, French, and even a

smattering of Russian. Oddly enough, in this, a novel written in English, none

of the brothers is conversant in that language.

Native to the island of Cephalonia, the brothers think of

themselves, primarily, as “Cephalonian.” They come from the town of Argostoli,

which even today has a population of only about 10,000. Born in the back of the

beyond, they must perforce leave home to make their way in the world. Giovanni

Battista (hereinafter abbreviated “G-B”) goes to the Italian mainland, where he

becomes a physician in Bologna and Turin. Eventually his renown as a doctor and

his academic accomplishments enable him to find employment treating those of

the high nobility, and he ends up in Paris, where he continues his scholarly

pursuits, researching books on the tapeworm and on various fevers. There he resides

at the time of the French Revolution. Marino, the self-proclaimed “black sheep”

of the bunch, trained as a military engineer, commits a crime of passion—he

murders an unfaithful mistress—and is forced to flee the Republic of Venice. Eventually

he finds himself in Russia, in the service of the empress Catherine the Great. Possessing

the same academic inclinations as his elder brother, Marco studies chemistry

and holds a university position in the city of Padua, where his chemistry

laboratory thrives.

There is another brother in the family, Paolo (1740-1813),

and a sister Maria (1735-?). Although frequently mentioned over the course of

the narrative, these two characters reside further back in the shadows,

approaching the anonymity of the book’s many secondary characters. The bright

lights of the narrative are reserved for the three principal Carburi brothers.

An even more hazy personage is the narrator of the novel,

who intrudes cautiously into the action to make a series of observations. On the

first page, e.g., she (let’s assume, for the time being, that she is a woman,

since the author is) visits Marino’s grave on Cephalonia. There she discovers

that the tombstone is no longer extant, but “on the now unmarked grave a

mock-orange bush henceforth flourished, scenting the air each April with its

fugitive, tender fragrance: Philadelphus is its Latin name. When I

searched for Marino’s grave, I could not find it, not guessing then that his

mortal remains must lie beneath that plant of brotherly love.” Huh? Wait a

minute. You just told us that you found the grave, and discovered a mock-orange bush planted

there, and now you say you could not find it? More on the narrative voice of

the book later.

Men Only

On the very first page the book’s structure is adumbrated.

Various details from different time periods will be woven together to make up

the narrative. There will be a lot of skipping around in time, but it all comes

together nicely in the end. We begin with a description of Marino’s birth,

attended only by women, but immediately there is a reference to his death, aged

53, at the end of the book; his funeral is attended, we are told, by men only.

Here we have a whiff of the eighteenth-century European attitude that colors

the entire book: womanly things are for women, and manly things for men. But

the men things are, ultimately, most important. Although written by a woman, The

Brothers Carburi has a point of view that is highly masculine. No book,

this, for ardent feminists, nor for cancel culture bigots or serious #Me-Tooers.

Born only two years apart, Marino and Marco behave almost

like twins. Among other things they enjoy doing is sharing the same woman

sexually. What about adultery? When the highly chaste and conservative G-B

visits his younger brothers who are studying in Venice, he “takes a precocious

Marino aside and points out firmly, ‘The only thing to be said about married

women is that if you make them pregnant it’s not too catastrophic.’” Marino

passes on this bit of “brotherly advice” to Marco, who later shares it with

baby brother Paolo.

The book is replete with secondary personages who poke their

noses, occasionally, into the narrative. These peripheral characters include by

far most of the females mentioned. Even the brothers’ direct sibling, sister

Maria—five years older than Paolo—plays little role in the novel. The same may

be said for the wives and daughters of the main characters: Paulo’s wife

Aretousa, Marco’s daughter Vittoria, G-B’s daughter Carlotta, and others. Odd

lacunae gape out at the reader in reference to these daughters and wives.

Marco’s wife Cecelia is featured mainly as a letter writer. She takes on the

job of composing soothing and gossipy missives to mother Caterina back in

Cephalonia, thereby relieving Marco of that task. Marino’s Greek wife Elena,

whom he marries in St. Petersburg, never comes totally into focus, but it seems

especially odd that her death—which precipitates Marino’s departure for Paris,

and, on the way there, the death of his beloved son Giorgio in a shipwreck—is

never explained. What did Elena die of, how did she die? We don’t know. Most

amazing of all, G-B’s wife, a young girl brought to him from Cephalonia at age

eighteen—in an arranged marriage when he is forty-five—is so insignificant a

character that we never even learn her name.

The only wife presented as a rounded character is Stephanie,

Marino’s second, French wife. Considering her little more than a common

prostitute—she has made her way through life largely as a kept woman—the family

never accepts her, calling her “Marino’s little tart.” At one point she asks

Marino about Cecilia, “What is she like?” “Don’t know. I’ve never met her,”

replies Marino. We readers never really meet Cecilia either, but we do get to

know Stephanie, since the author uses conversations between her and Marino to

move the narrative action along. More on this later.

Peripheral female characters abound; as if the author were

telling us, “Of course they are peripheral; women in Europe of the eighteen

century were peripheral. Besides Stephanie, the only other strong female

character is the matriarch of the family, Caterina Carburi, who comes originally

from the island of Corfu. Caterina overshadows her husband in the narrative and

seems to have had much more influence over her sons. (“If I have made little

mention of their father, Demetrio, this is because he never figured as

prominently as their mother in his sons’ imagination),” [writes the narrator

parenthetically].

So, in an odd twist, although this book is dominated by

males and male perspectives, the paterfamilias of the family turns out to be a

ghostly figure in the background, which is populated mostly by spectral females.

His death not even a third of the way through the book (see p. 91-93) causes

little in the way of grief on the part of anyone, and seems, in fact, to

confirm a situation long prevalent—the first son, always dutiful and reliable G-B,

is the real father figure: the big brother as parent. In a universal pattern

that is too common to be entirely coincidental among siblings, the dutiful

firstborn is his mother Caterina’s favorite; the scapegrace second son bears

the brunt of her perpetual disgruntlement, and does his best, so it seems, to

live up to that role.

A development bound to outrage feminist readers and the cancel

culture crowd most of all is Marino’s treatment of his daughter Sofia. This is,

in fact, something that would outrage any right-thinking person. When Marino

first begets a child he assumes, automatically, that this will be a son, and he

goes out to celebrate the begetting not with his wife Elena, but with a ballet

dancer. To his disappointment, the begat later turns out to be a daughter,

Sofia. Soon, however, the long-awaited son, Giorgio, arrives, and soon he is

the apple of his father’s eye; he becomes, in fact, something like a best

friend to his father.

After Giorgio’s accidental death both Marino and Sofia, his

only surviving child, are aware that if he had a “Sophie’s choice”—i.e., if he

could have chosen which child would die, he would most certainly have chosen

Sofia. After their move to Paris he soon shuffles her off into the household of

his brother G-B, in effect, rejecting her as his own. Usually not one to take

sides or express strong opinions, the narrator rightly opines at this point,

“It is scandalous to take no interest in one’s own daughter.” As if this were

not bad enough, upon his move back to Cephalonia late in the book, where he

undertakes an experiment to grow crops common in the New World, indigo and

sugar cane, Marino abandons Sofia altogether and disinherits her. He leaves everything

in his will to his new wife Stephanie, who, in the opinion of the family, “is

little more than a common drab.” The human psyche works in strange ways. It

seems almost as if Marino’s shabby treatment of his daughter is something of a

payback to her, for not dying in place of beloved Giorgio.

One last thing about the masculine perspective that

dominates throughout: could the author be doing something not often attempted

by writers of fiction? Could she have employed a male narrator to tell the

story? This possibility is suggested by my use of “she/he” below, when referring

to the narrator.

The Epistolary Novel

The Brothers Carburi is not exactly an epistolary

novel, but then, in a way, it is. The narrative method does not involve

directly quoting verbatim the many letters written by the brothers, to

colleagues, to their mother, and, especially, to each other, but those letters,

researched by the author, provide most of the material that makes up the book.

In a prefatory note in the front matter she thanks Anastasios Charbouris “for

entrusting to me a treasure trove of Carburi family letters and documents. From

these threads have I woven my fiction.”

The book is replete with passages about the writing and

receiving of letters. At an early age Caterina’s three oldest sons leave home

for foreign lands, and her mood often hinges—for whole decades of her life—on

what they write to her. “Countless women with wayward lovers know the longing

anticipation with which letters are awaited, the restlessness and irritability

of weeks or months when none arrive, the secret joy of days when they do.

Caterina had never in her life had a lover yet was familiar with these

feelings; when she received letters from her sons—and particularly from her

eldest son—the glow of happiness made her footsteps lighter and her back

straighter for days at a time.”

Here’s a passage about how communicating through writing

letters differs from face to face concourse: “But of course there are things

that you could say to someone face to face yet would never think of writing in

a letter: perhaps this is simply due to the fact that you cannot see the person

you are addressing or that you cannot be sure that his will be the only eyes to

read what you write, or maybe it is because you are always aware of the time

that must pass before the letter will arrive (which makes you less hasty, more

reflective and temperate).”

Marco worries about the blank space on the pages of his

letters to his mother and enlists his wife to help fill that space in: “More

pages could be added if need be, but too much blank space makes letters look a

bit meagre, so that Marco was extremely grateful to Cecelia for her ability to

come up with enough gossip and news and affectionate sentiments to fill the

sides decently.”

At times the omniscient narrator tells us not only what the

brothers write in their letters, but also what they contemplate writing and how

they hold their mouths as they write. Worried about his brother Marco’s health,

“Marino thought of writing, ‘I beg you to take care. Many people here have died

of the croup this winter,’ but decided not to, probably because to think such

thoughts, let alone write them on paper, amounts to a sort of tempting of

providence. Thus instead he continued, ‘My heart will not be easy until I have

news of your recovery.’ . . . A pause at this point as Marino waited for the

ink to dry, after which he turned over the page and began to answer his

brother’s questions.” I like that pause in the narrative, the ellipsis, while

we the readers, along with Marco and the author, wait for the ink to dry.

The narrator sometimes takes advantage of her/his position

of omniscience to describe even letters imagined but not written. “‘My dearest

brother,’ Marino wrote—then paused, for he found all of a sudden that he

couldn’t tell Marco about Stephanie: an uncomfortable realisation that he was

no longer sure his brother would instantly understand. He shook his pen

impatiently, thus causing a little trail of ink blots to scatter diagonally

over the paper which with a few penstrokes he rapidly transformed into the

pupils of a series of wide, watching eyes, sighed, threw this sheet away and

started again with an equally personal though less controversial subject.”

Could those wide-open eyes be emblematic of the eyes of us, reader and author,

looking over Marino’s shoulder as he writes?

The narrator’s own characters later create problems for her/his

researching self. After the breach with Marino—over his decision to marry a

woman they find unacceptable—G-B, and later Caterina, burn some of the

materials that could have gone into the making of this book: Marino’s letters

to them.

Sad to say, all that we as modern readers learn in this book

about the writing of letters is wasted on us now, since we live in the age of

the Internet and the e-mail, and practically nobody writes letters anymore.

Playing the Game of

Omniscience

Putting together a fiction book based largely on researching

written correspondence creates a number of technical problems. Constructing

such a novel is not as hard as raising a monumental rock in a marshland and

transporting it to St. Petersburg, but ways must be figured out to get the

structure right. Happily, the narrative voice of the book tiptoes successfully

around these difficulties and produces a well-structured artifact. Some of the

action of the novel is moved along by imaginary conversations between Marino

and his second wife Stephanie. We get a lot of passages such as “Marino later

told Stephanie.” To a lesser extent this same method is applied to

conversations between Marino and his son Giorgio. As noted above, Marino’s

first wife Elena, the Greek woman he marries at age thirty-six in St.

Petersburg, remains, largely, a cipher, but scenes describing Stephanie’s

interactions with Marino enable the author to make a rounded character of her.

Mentioned early on, Stephanie comes into focus gradually—we

do not even learn her surname, Vautez, until two thirds of the way through the

narrative. Her visit to the family home in Cephalonia and the cool reception

she receives is described before we know much about her—but by the end of the

book she has become a central, and sympathetic character.

Not easy to do, making sympathetic this woman, who at one

point informs Marino that “There’s nothing wrong with sleeping your way to

where you want to be.” The narrator cannot reveal things about Stephanie

through the letters she writes, since Stephanie does not write letters. Rather,

the narrator builds this sympathy largely through the card of omniscience,

which she/he holds but plays delicately.

The cautious attitude toward omniscience that prevails all

through the novel begins early (on page 6) with the following problematic passage

in parentheses: “(I have no wish to invade Giovambattista’s privacy and shall

thus try in what I write to respect some of his secrets: his dignity—always a

vulnerable spot—was precious to him and, like most people, he hated being

laughed at.)” The narrator’s professed attempt to keep at a distance from the

narrative is often belied by little personal asides that remind us of her/his

presence: “It occurs to me,” or “It seems to me,” or “It does occur to me,

though.” The passage at the very beginning of the book, about finding Marino’s

grave, or not really finding it, is a tip-off to the ambivalent—or cagily

prevaricating—stance of the narrator throughout. As if to suggest, “I’m sort of

in the book, while trying not to be in it. I’m tactful, you see.” Here’s her/his

take on the murder of Marino: “Since there is no way to avoid writing of

Marino’s death, I shall state quite simply . . . . that Marino died as a result

of twenty-seven knife wounds.” Again, as if to say, “I’d really rather not get

into this gruesome business, which offends my delicate sensibilities, but,

anyway, he was stabbed a total of 27 times.”

As for the early promise to respect poor G-B’s privacy, the

narrator sometimes breaks the bonds binding her/him to the letters as source

and does what any omniscient narrator of a fiction does: makes things up.

“Turin as a matter of fact was also the place where in due course he finally

lost his virginity—technically speaking, that is to say, for none of his

various amorous encounters had hitherto involved the penetration of another

human being—although neither his brothers nor his friends nor anyone else ever

learned anything of the extraordinary happiness that this occasioned. (There

were a great many well-guarded places in Giovambattista’s mind.)”

With what a preponderance of omniscience is that passage

freighted! As if to say, “Well, in for a penny, in for a pound; I’m trying hard

not to be omniscient, but if that’s the only way. No one knows how he lost his

virginity, but I know, gentle reader. I also know about all his other amorous

encounters, and I know that he never had penetrated anyone previously, and I

know that when he did he was extremely happy. I know all these secrets, which

he kept hidden from the world his whole long life, and now you, gentle reader,

know them as well. You may ask how I know them. Well, because I looked deeply

into my character’s soul, and then I made those facts up.”

At one point G-B’s sexual orientation is called into

question; his brothers ponder whether he might possibly be homosexual: “I mean,

do you think he actually beds his [men] servants?” [asks Marino]. “Marco . . .

did not pretend to be shocked, but considered the idea carefully in the light

of his recent stay in their brother’s household. Then, ‘No,’ he pronounced

stoutly. ‘I am quite sure he doesn’t.’ (In this, as it happened, Marco was

perfectly correct.),” reassures us, parenthetically, the omniscient narrator.

One more example. The narrator reveals that G-B has a second

account book or diary. “I have hesitated to mention it since this small

notebook was extremely private, its very existence being unknown even to his

servants: in it were entered expenditures of a bodily kind.” We learn elsewhere

in the book that the taciturn and prudish G-B, who, unlike his brothers, avoids

human sexuality, is leery of wasting his precious bodily fluids. Much to his

brothers’ amusement, he advises them at one point that “Too regular a practice

of the generative act cannot fail to have a deleterious effect on the health of

both man and woman.” This leitmotif of the expenditure of bodily essences shows

up several times in the narrative, and concludes, sadly, with the expenditure

of Marino’s blood when he is stabbed to death.

So much for the pose of tactfulness, the promise to respect G-B’s

secrets and preserve his dignity. Here the stance of omniscience becomes

something like a joke on the part of the author, who describes a fastidious narrator

reluctant to intrude, but, occasionally, intruding with mad abandon. As for the

characterization of Stephanie, the omniscience is used quite skillfully to

create her as a personage. The narrator does with Stephanie what she/he much

more infrequently does with other characters: goes into the character’s mind to

tell us what she is thinking. “‘Nothing is permanent in life,’ Stephanie told

herself firmly more than once; nevertheless, the most amazing fact of all—that

he [Marino] appeared to want her company and conversation on a regular

basis—seemed to be one of those unexpected blessings that you might very well

go down on your knees and thank God for.”

Another example: “And perhaps Valliano was not impervious to

her charms for much, much later, when Giovambattista and Marco were preparing

to sue Stephanie, to reclaim the share in their family lands that Marino had

foolishly left her . . . he was the only member of the family who maintained

some contact with her . . . and no one ever knew that Stephanie had

considered—but rejected—the possibility of encouraging the young man into

closer relations.”

This usage of the phrase “No one ever knew” is, in effect, a

way the omniscient narrator has of taking the reader into her/his confidence.

Late in G-B’s life, when he is caught in the turmoil of the French Revolution,

“Certainly no one ever knew anything of the way Marino began to intrude

repeatedly into his elder brother’s thoughts during that wretched time in

Paris.” As if to say, “But I know, and now you do as well, gentle reader.”

At times the delicate narrator seems to be saying that there

are things even omniscient she/he cannot know. For example, when Marino and his

mother go head to head over what Caterina sees as the disgraceful marriage to

Stephanie, the narrator refrains from telling us exactly what was said. “Since

neither Marino nor his mother spoke of this interview to anyone, whatever was

said remained between the two of them.” But then a mere three pages later the

narrator cannot resist being omniscient again: “‘They can like it or lump it,’

was what he reflected with a private shrug—it being wiser not to voice such a

disrespectful thought—when his mother spoke sharply of the offence caused to

all decent-minded people by what she called ‘your deliberate misalliance.’” Ah,

so there was a fly on the wall in that scene after all!

What does all this playing around with omniscience in the

narrative amount to? A kind of private joke between author and reader, a streak

of humor that underlies what is, largely, a serious narrative.

Plotlines

The Brothers Carburi describes, largely, how three

brothers from Cephalonia make their way through the haze of the eighteenth

century. The haziness is a result, partly, of the author’s decision to omit

giving the years in which certain events take place. The reader does not learn

the dates of the main characters’ lives—provided at the beginning of this

review—until reaching an appendix at the very end of the book. Of course, a

certain time frame may be deduced, in that a few well-known historical events

are mentioned: e.g., the French Revolution and the unveiling of the most famous

monument in all of Russia: The Bronze Horseman.

Also somewhat adrift in the haze are the many secondary

characters, some of them directly related to the three Carburi boys (wives,

daughters), others their friends or acquaintances (Father Giacomo Stellini,

Antonio Vallisneri, Father Atanasio Peristiano, and others). This is not to

indict the author for failure to bring such characters directly into the

action; she has chosen to concentrate on the three main protagonists, and

others are necessarily ancillary.

Certain central events stand out, among them two different

murders, both in which Marino is involved. After his mistress is unfaithful, he

confronts her, is taunted, and strangles her. This results in his fleeing Italy

and going to Austria. After his brother G-B—ever the manipulator and ever

blessed with connections—sends out a few letters, Marino ends up in Russia,

where he is well received and where he works as a military engineer.

The author is particularly good at describing the feelings

of a murderer subsequent to the crime, and of those close relatives who protect

him. All, it seems, is rationalization. Later on, “Marino thought of his

mistress’s death as ‘something that happened,’ rather than ‘something that I

did.’” He falls back on certain catchwords: “She got what was coming to her. It

served her right.” You cannot help thinking of O.J. at this point, especially

given that the woman uttered certain wounding words, goading Marino into the

act. From what we know of the O.J. case, so did his wife Nicole. If there is a

lesson to be learned for the woman here, I suppose it is this: when caught

betraying a lover or spouse, never get defiant or sarcastic, be humble; and

never, never impugn the size or efficacy of the wronged man’s middle leg.

This tendency toward rationalization does not mean that the

murderer feels totally guiltless for his crime; far from it. Later, much later

in the book, Marino himself is murdered. Since he attributes certain

tragedies—such as the death of his son Giorgio—to destiny’s payback for his

having committed murder, he may well have opined that he too “got what was

coming to him”—were he alive to speculate on how he died. At the time he is

killed—by five assassins with knives—Marino has moved with Stephanie back home,

to Cephalonia and the marshes of Livadia. There he is involved in an experiment

in agronomy, trying to grow indigo and sugar cane. We never learn much about

the motivations of his killers, men he has hired to work for him, although

there are hints that he has mistreated his workers, and may have offended

residents of the marshlands, who, along with their sheep, were evicted when he

began draining the swamps.

What else do the brothers Carburi do with their lives? Well,

each of them is successful, G-B as renowned physician and scholar (in Italy,

and, later, in Paris), Marco as well-respected chemist (in Padua), and Marino

(in Russia) as military engineer and mover of The Rock (more on The Rock

later). Each of them makes a marriage and has children. At one point we are informed

that, at age 41, 34, and almost 33 the three are not yet married. This is

surprising, given life expectancy in the eighteenth century; it reached 45 only

at the beginning of the twentieth century. If you hoped to leave descendants

you should have been propagating the species early on. Only at age 45—this

would be in the year 1767—does G-B decide he needs a wife.

Odd, given that he as a physician certainly realizes that

the health hazards of the times often made for brief lives. Then again, he is

consistently portrayed as a prude and as one uncomfortable with sex, so this

may explain his tardiness. Or did he assume that all he knew about the practice

of medicine would improve his chances for a long life? Always worried about

finances, always taking precautions, G-B, of course, does not see the French

Revolution coming. Caught in the midst of the terror in Paris, he is in great

danger, given his close association with royalty. Later his life is impacted

financially in the aftermath of the Revolution, and, threatened with penury,

he, at age 75, takes a university position, the Chair of Natural Science, once

held by his friend Vallisneri, in Padua. At any rate, he did live a long life,

dying in his eighties.

The Rock and the

Marsh

Fleeing Western Europe after having committed murder, Marino

Carburi ends up in St. Petersburg, Russia, during the reign of Catherine the

Great (in power, 1762-1796). He considers it wise not to use his real name in

Russia, adopting the name “Alexander Lascaris.” Exactly where he came across the

surname he borrowed we are never told. While still in Vienna he starts signing

his letters “Alexandre de Lascaris,” and has begun learning French. Very soon

he has also awarded himself a title, and “his fellow-officers in Austria knew

him as the French-speaking Chevalier de Lascaris.”

Arriving in St. Petersburg, Marino connects with fellow

Cephalonians who are highly placed and can help him find a position. They do. Soon

a “slight hiccup” occurs when he comes “face to face with a gentleman who

rightfully bore the name Lascaris.” Thinking fast on his feet, Marino says,

“‘Much as I would be honoured by the connection, I cannot pretend to claim any

legitimate relation with Monsieur Lascaris’ (a disarmingly rueful smile, an

extremely polite bow and a very slight emphasis or fractional pause before the

adjective, implying that unavoidable kink in the lineage which has to do with

bastardy).”

Of course, he fools no one in the Russian court, including

the Empress herself, who later refers to him as “that little Greek officerik

of yours.” The “yours” here refers to Ivan Betskoi (Бецкой in Cyrillic), who becomes a patron

of Marino and later encourages him in his engineering project to move The Rock—known

as Thunder Rock. The first mention of Betskoi—referred to in this novel always

as “General Bezkoy,” possibly the spelling Marino used in his letters—comes,

interestingly enough, only a page after mention is made of Marino’s

pseudo-bastardy. Interesting, because that mark of bastardy could be the very

thing that got Marino into Ivan Betskoi’s good graces.

One of Catherine’s most influential ministers, Ivan

Ivanovich Betskoi (1704-1795) was the illegitimate son of Prince Ivan

Trubetskoi, a Russian field marshal. His father had no other sons and Betskoi—while

always using the truncated surname that denoted bastardy—was educated in the

European aristocracy. Spending much of his youth in Western Europe, he was on

very close terms with Catherine’s mother, and even was rumored to be the real biological

father of the woman who would come to be The Great. Accounts differ as to what

extent he was involved in the conspiracy that deposed Tsar Peter III, murdered

him, and brought to power his wife Catherine in 1762. At any rate, Betskoi was

one of her trusted advisors for years and held many important posts in her

administration. He was much involved in educational reforms, and it was he who

commissioned the sculptor Etienne Falconet to create for her the statue of

Peter the Great, known later as The Bronze Horseman.

Soon Marino’s career in Russia advances. “‘I have been

appointed Director of the School of Cadets . . . and hold the rank of

Lieutenant Colonel,’ [or later], ‘I am now Aide-de-Camp to General Bezkoy, who

is in charge of all public buildings and construction works.’” When

Marino—Monsieur de Lascaris—comes up with his plan to transport what will be

the pediment for Falconet’s statue—a granite monolith lying in marshland off

the Gulf of Finland—to St. Petersburg, the immediate response is mockery. In

most minds his scheme most likely occupies the same place as did that of Franz

Leppich, the Dutch peasant who built, for Tsar Aleksandr I, a hot-air balloon

intended for waging air warfare on Napoleon. Leppich’s balloon never got off

the ground (see mention of this episode in Tolstoy’s War and Peace). But

Marino has powerful allies, first of all Betskoi, and then “the Empress herself

who had the final word,” and her word was this: “Let the little pseudo-Lascaris

try.”

The leitmotif of the marsh runs throughout the book as a

whole, as the narrator alerts us early on (p. 9): “Then there is another

underlying image, existing on a level beyond language, which is that of the

marsh. This is a powerful and abiding image, for Marino’s triumph and later his

death had to do with marshes. If Marino is remembered at all today in his

native land it is by the official name still given to an empty, lonely place:

Carburi’s marsh.” Marino’s triumph is an engineering feat. He manages to raise

Thunder Rock out of marshland adjacent to the Gulf of Finland and transport it

to St. Petersburg. While in the marshlands of Russia he dreams of Lixouri—second

largest town on Cephalonia—and the marshlands of Livadia to the north of it,

where many years later he will be murdered while pursuing his plan to grow

crops there.

The lifting and moving of The Rock is described in technical

detail, mostly in letters that Marino writes to his brothers and in

conversations with his son Giorgio. Although the pediment of the statue (The

Rock) has a central role in the narrative of the novel, little is said about

Falconet’s statue of Peter the Great—the most famous monument in all of Russia.

Given that Marino is an engineer, difficulties involving engineering are

prominent in discussions of the statue. A man named Figner is mentioned once,

he who “came to Russia to make the armature for Monsieur Falconet’s statue”—an

armature being “a sort of metal skeleton around which the artist builds his

model.” Marino informs his son Giorgio that the fact of the rearing horse

presents problems: “If the horse had all four hooves on the ground it would be

a lot easier.” This technical difficulty is overcome, partially by using the

snake being trampled beneath the horse’s hoofs as another point of support.

Marino later tells Giorgio as well about the prototype for

“the Great Peter’s horse . . . Lisset,” and how Falconet brought in two horses

from the stables of Count Orlov and had them rearing for him again and again as

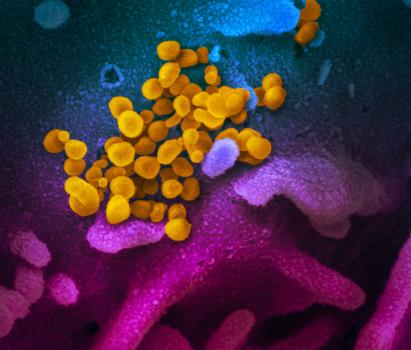

he made drawings. No mention is made of the head of Peter on the statue, a

magnificent work in itself, and done by Falconet’s assistant, a precocious

eighteen-year-old girl named Marie-Anne Collot. Last I heard, by the way, the

prototype horse, ridden by Tsar Peter at the Battle of Poltava—usually spelled

Lisette (Лизетта in Russian)—is still around, stuffed and rather worse for the

wear, in the Zoological Museum, St. Petersburg.

Marino never sees The Bronze Horseman on the rock he worked

so hard to bring to St. Petersburg, as he has left Russia for Paris by the time

the statue is unveiled (August 7, 1782). His younger brother Paolo, however, is

there for the unveiling but never describes it in letters, as Paolo proves to

be “an appallingly erratic correspondent.”

After moving to Paris Marino writes a book about The Rock,

and G-B contributes the appendix. The title of the book is given as Monument

élevé à

la Gloire de Pierre-le-Grand, which makes you wonder: is this a book about

Falconet’s statue, rather than what we are expecting, a book about its pediment?

A quick check on the Internet reveals that the title is much longer (in my

translation from the French): or a Narrative of the Labor and the mechanical

Means employed to transport to Petersburg a Rock . . . destined to serve as the

Pediment for the equestrian Statue of that Emperor.

Conclusion

Read the letters (real) of the Carburi brothers, listen to

the (fabricated but logical) conversations they have with children and wives

and you learn a lot about how things were done in Europe in the eighteenth

century. You learn, e.g., from G-B’s work how a physician treats an illness.

Bloodletting is still much in favor, but a good doctor, it seems, already

relates to patients in much the same way that a good doctor does today. Certain

psychological insights about a multitude of issues flash their way into the

narrative. Take this: the encounter between a good-looking male physician and

his female patient “perhaps exists in the narrow, shadowy space that lies

between the definitely non-erotic and the possibly erotic.” The first inoculations

against smallpox, called “variolation” are mentioned. G-B resists them at

first, considering such practice too risky, but Catherine the Great herself was

eventually inoculated.

The book abounds with fascinating information. Want to learn

about tapeworms and how they were treated in the eighteenth century? This is

the book for you. Want to learn what you hear when you hold a conch shell to

your ear? What’s special about the number 9? How to move a big rock? Wonder who

the woman was who learned to cultivate indigo in America? Her name was Eliza

Pinckney. Eighteenth century dress codes are mentioned, and we are often given

detailed descriptions of how the fastidious G-B dresses. Example: “a discreetly

sumptuous waistcoat of embroidered snuff-coloured velvet.” Women of the time

did not yet wear undergarments on the groin.

As for the principal narrative itself, the story of the

three brothers, its climax comes when Marino, intent on marrying a woman, Stephanie,

whom his relatives will never accept, breaks the “unspoken fraternal taboo” and

speaks with utter disrespect to the father figure of the three, G-B. He says

things that he may have been thinking for years, but things that should never

be said to a brother. In anger he disparages his elder brother’s touchiness

about sexuality and claims that when he, G-B, at age 45, married an

eighteen-year-old, the vicious talk around town was whether G-B could “get it

up on his wedding night.” The breach that comes of this conversation can never

be healed, is never healed.

What do I like best about this book? I like a lot of things

about it, but I like best the way the author loves words. Here is a description

of what G-B, or any good physician, should be doing: “wrestling with obdurate

diseases and overpowering them with an armamentarium—a good word, this—of

powerful medicines.” The author loves words. Is there a better reason for

writing creative literary fiction than a love for words? No. There is no better

reason.

The Bronze Horseman, Detail: Head of Horse and Peter the Great's Right Hand