The Icon and the Axe

Among American scholarly works on Russian history and

culture perhaps none ranks higher than James H. Billington’s monumental, The Icon and the Axe: An Interpretive

History of Russian Culture (Alfred A. Knopf, 1966). Billington chose this

title because for him “Nothing better illustrates the combination of material

struggle and spiritual exultation in Old Russia than the two objects that were

traditionally hung together in a place of honor on the wall of every peasant

hut: the axe and the icon.”

Billington goes on to outline briefly the symbolic

importance of these two objects throughout Russian history. Much of what he

says has direct application to the plot and themes of Crime and Punishment. Pre-Christian tribes in what was to become Russia

used axes for money and buried them ritually with their owners. Even after the

coming to Russia of Christianity in 988 AD the axe remained important as the

primary weapon in close-range fighting and the implement used by frontiersmen

to fell trees and build structures.

Russian proverbs make frequent reference to the axe: “The

axe is the head of all business; “You can make it through all the world with

only an axe.” Here are a few more in Russian: “Мудер, когда в руках топор, а без топора не стоит и комара (roughly:

he’s a real wise guy with an axe in his hands; take away his axe and he’s a

buzzing mosquito);” “Без топора по дрова не ходят (Don’t

go out chopping and leave your axe at home;” “Мужика не шуба греет, а топор (It’s

not a fur coat warms a peasant; it’s an axe).”

When you are astounded by something someone has done or said

you say, “Меня как обухом по голове (literally:

It’s as if someone hit me on the head with the blunt end of an axe).” Which is

exactly what the old usurer lady in C and

P must have had ringing through her mind, since she was literally hit on

the head with that blunt end.

As the Russians consolidated their new civilization in the

Upper Volga region after the coming of Christianity and began spreading out to

the eastern frontier, they used the axe to hack out clearings, to fell trees

and build fortifications. Only in relatively recent times historically were

nails widely used in building, let alone saws and planes.

The peasants used

axes for terrorizing the landed nobility in uprisings throughout early Russian

history, and the tsars used axes to put down the uprisings.

The axe was also “the standard instrument of summary

execution . . . . Leaders of the revolts were publicly executed by a great axe in

Red Square, Moscow, in the ritual of quartering. One stroke was used to sever

each arm, one for the legs, and a final stroke for the head” (Billington).

The axe was always associated with political rebellion, and

here is where the instrument as used by Raskolnikov in C and P is especially appropriate. Several critics have pointed out

that Raskolnikov’s act of murder is symbolically an act of political

revolution. He chooses to kill someone who has no political significance, but

he is inspired to do so by political ideals and rhetoric of the radical left of

the times.

In the early 1860s, at the very time that Dostoevsky was formulating

his plans for the novel, the radical thinker Dobrolyubov was summarizing the

Utopian Socialist program of his colleague and friend Chernyshevsky’s book, What Is To Be Done? as “Calling Russia

to Axes.”

Both Notes from the

Underground, the work of fiction published directly before C and P, and C and P itself are vehement polemics with Chernyshevsky’s ideas and

principles. No doubt Crime and Punishment

is in some respects a political allegory, suggesting the danger of radical

ideas when some misguided someone decides to act upon them.

By the late 1860s the notorious revolutionary Sergei Nechaev

had set up a “secret society of the axe.” Dostoevsky died in January, 1881, and

in March of that year the terrorist group known as “People’s Will” achieved

their greatest triumph when they succeeded in assassinating the “Tsar Liberator”

Aleksandr II. They used bombs, however, rather than axes.

This was already the

sixth or seventh attempt on the tsar’s life, the first being in 1866. It was as

if that murder were in the Russian air, and Russian history could not go on

until it was achieved. Despite all of Dostoevsky’s writings—both fiction and

nonfiction—about the wrongheadedness of radical left dogma, the dangers of

putting such dogma into practice, the ideas had a momentum of their own, moving

almost inevitably along until the October Revolution of 1917.

If you read the testimony at the trial of one of the

perpetrators of the assassination in March, 1881—a man named Andrei Zhelyabov—it

sounds as if one of Dostoevsky’s characters were talking, spewing out

revolutionary slogans but throwing in a love for Jesus Christ in the bargain.

Later on, in the early years of the Russian Revolution, the great poet

Aleksandr Blok put Christ at the head of a group of marauding revolutionary

sailors, in his controversial poem, “The Twelve.” [On Zhelyabov, see Norton Critical

Ed. of C and P, p. 559]

Written at the dawn of the twentieth century, Anton Chekhov’s

play, The Cherry Orchard, emblematic

of the end of the landed nobility in Russia, and even foreshadowing the end of

Imperial Russia itself, concludes with the sounds of an axe, chopping down the

trees in the orchard. The image of the axe carries over into Soviet times, since

in 1940 the most brilliant of the men who made the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917,

Leon Trotsky, was assassinated in Mexican exile. He was hit over the head with

an ice axe, which remained implanted in his skull.

While researching demographics and health issues in the

Soviet Union, the American scholar Murray Feshbach discovered that the most

common murder weapon in the country was still the axe. There had always been

strict gun-control laws, and Soviet society was still quite rural, so the axe

tended to be the weapon most accessible to the average Russian.

As for the

modern Russian Federation, I have not seen statistics about murder weapons. One

thing for sure: firearms in Russia are still tightly controlled. If the Russian

Federation had the kind of gun laws that the U.S. has, the whole country

probably would have been wiped out by now.

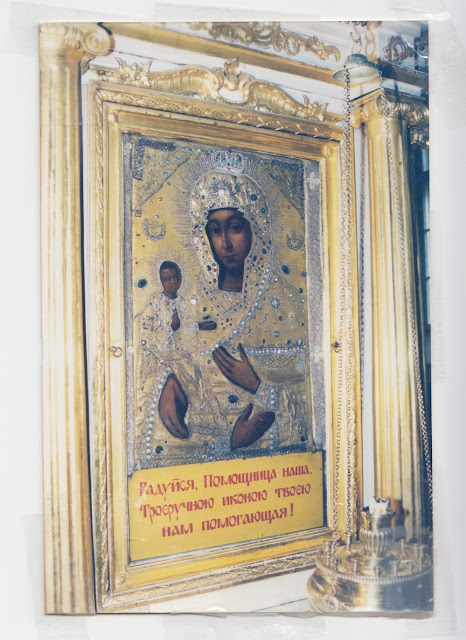

Billington’s other overriding symbol of Russia, the icon or

religious image, is also directly relevant to Raskolnikov and major themes of C and P. Raskolnikov’s inner struggle,

the dominant theme of the novel, is really a struggle between the icon and the

axe. After he kills the old pawnbroker he throws down the icons or crosses on

her body, symbolically rejecting the Russian Orthodox Christian tradition that

was so important to him in his childhood. Of course, if we are to believe the

rays of brightness that shine into the epilogue, the saintly Sonya will

eventually win Raskolnikov over, turning him from the path of the axe back to

that of the icon.

No comments:

Post a Comment