Motivations

Why did he do it? This is the central question of C and P, which is a murder mystery, but

not what they call a “whodunnit.” This novel is a “whydunnit,” or a “I-done-it-but-I-don’t-know-why-I-dunnit.”

Of course, in all of Dostoevsky’s fiction characters are ruled by subconscious

impulses that they themselves are unaware of. Raskolnikov is mired in the

cyclical processes of human reasoning, which Dostoevsky, the great

anti-rational rationalist, treats with suspicion.

So, as one critic, Phillip Rahv, has put it, Raskolnikov is “the

criminal in search of his motive” (Norton Critical Ed., p. 540-41). Why did he

do it? The full complexity of the issue becomes manifest only about halfway

through the book (Part 3, Ch. 5; p. 218-25 in the Norton Critical Ed.), when,

for the first time we hear about the article he has published on crime. Much to

the surprise of Raskolnikov, who was not even aware that his article had been

printed, the police inspector, Porfiry Petrovich tells him that he has read it.

The central point of the article is that human beings are divided into the

ordinary and the extraordinary. The ordinary are like sheep, baaing their way passively

through life, but the extraordinary have the right to overstep the boundaries

of morality and law, to commit immoral acts in furtherance of their majestic

goals. This overstepping provides the title of the novel, Преступление и наказание—the

word for ‘crime’ in Russian, at its root meaning, suggests a “stepping across,”

akin to the word “transgression” in English.

In his conversation with Sonya (Part 5, Ch. 5; p. 348-54),

Raskolnikov’s confusion about his motive becomes apparent, when he goes through

nearly every possible motivation for his crime, rejecting or revising each of

them on the fly. Svidrigailov, who is conveniently eavesdropping on this

conversation, later recapitulates the motivations to Dunya (Part 6, Ch. 5, p.

415). Here is roughly how the process goes in Raskolnikov’s feverish mind.

I did it because I was poor and I needed money to launch my

career, but no, what I really wanted was to help my mother and sister and,

after all, I had just received a letter from my mother describing how my sister

Dunya was about to prostitute herself by marrying a despicable character,

sacrificing herself to help me, but no, it wasn’t really that, what I wanted

was to get money so that I could go about doing good, working toward the

eradication of human evil and social inequality on earth, and I figured that by

killing one contemptible old woman, who nobody on earth needed and who soon

would die anyway, I could get that money and then atone for this one transgressive

act by doing great good for the rest of my life, and, besides that, I was,

after all, insane, or nearly insane, going nuts lying here in that cramped

coffin of a room and actually physically ill as well, feverish, not even aware

of what I was doing, but no, it wasn’t really that, what I wanted to be was a

great man, a man who can transcend commonplace vulgar morality and become a

superman, prove that he is above the ethics of the stupid baaing herd, a

Napoleon, and I really could have been a Napoleon, I’ve got the stuff for it,

but no, really I’m just a common louse like everyone else, but I had to know, you see, it was an experiment, I

had to find out if I was a man or a louse, I had to know whether I really could

overstep the bounds, whether I could

do something that ordinary men are not capable of doing, and I didn’t really

care about my mother and sister or the money, it was just the principle of the thing, and you know

what’s the most despicable thing of all? By collapsing emotionally and

physically the way I have, all I’ve really proved is that I’m a louse after

all, Napoleon would have done it without even thinking about the sleaze of it,

the immorality, he wouldn’t have worried for a moment about the ethics of the

thing, he was beyond mere morality, a superman, but me, I’m a louse, and yet

maybe I judge myself too soon and too harshly, maybe I still have great things

in me, maybe I’m not a louse after all, yes I am, no, you’re not, etc., etc.,

etc., the round and round goes on.

In addition to the reasons Raskolnikov himself lays out,

only to keep rejecting, there are several other possibilities: (1) His mental

illness as the primary motivation. Certainly he would not have committed murder

had he been in a balanced state of mind; (2) The idea that he is consciously

seeking suffering. The “punishment” of the title operates even before he

commits the crime, and he is punished in his own agonizing mind long before he

is convicted and sent to Siberia. In this novel, as in so much fiction that Dostoevsky

wrote, much is made of suffering as a means of purification of soul. Marmeladov

says that he drinks not to relieve himself of guilt, but in order to redouble

his sufferings. The peasant Mikolka, though not guilty, confesses to the crime

in order to “accept his suffering” and suffer his way through to some

redemption. As Porfiry Petrovich remarks, Mikolka is a “religious schismatic,”

which in Russian is “iz raskol’nikov.”

The very similarity of the word ‘schismatic’ with Raskolnikov’s surname suggests

that this character is an alter ego of Raskolnikov. In fact, in summing up the

possible reasons why Mikolka confessed (Part 6, Ch. 2, p. 383), Porfiry

recapitulates Raskolnikov’s reasons for committing the crime. He ends up, once

again, with suffering:

“Do you, Rodion Romanovich, know what some of these people

mean by ‘suffering’? It is not suffering for somebody’s sake, but simply ‘suffering

is necessary’—the acceptance of suffering . . . . . . Mikolka desires to ‘accept suffering’ or

something of the sort . . . . . What, can’t you admit that such fantastic

creatures are to be found among people of this kind?”

(3) The issue of suppressed sensuality. Some psychological

critics of Dostoevsky have suggested that Raskolnikov is, above all, a

passionate character who has suppressed his own libido. In the text of the

novel he is certainly a prude, and he reacts with revulsion to Svidrigailov’s

openly expressed sensuality, his love for anatomy above all else. These same

critics assert that one way Raskolnikov has of working out his repressed

sexuality is murder. They comment on the sexual symbolism of the murder of two

women, calling this a kind of sublimated rape.

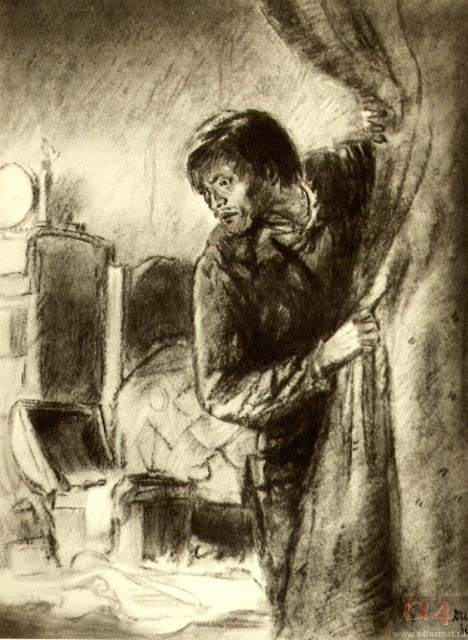

Maurice Beebe mentions the succession of events just prior

to the murder: the episode in which Raskolnikov encounters a drunken girl on

the street, and saves her from a lecherous dandy pursuing her, followed by the

mare dream (murder of a female horse), followed by his own acts of murder:

“The progression from seduced girl to beaten horse to

murdered pawnbroker [and her sister] tells us much about the strain of aggressive

sexuality that lies within Raskolnikov, a taint which he himself denies on the

conscious level” (Beebe in Norton Critical Ed., p. 591).

In the epilogue of the novel Raskolnikov still struggles with

motivations for his act. He is still suffering his way through to some kind of

redemption, but we do not know if he will ever get there, because Sonya’s God

of meekness and love still struggles in his soul with the devil of his pride.

At any rate, by this late point in the novel it seems clear that the “superman

motive,” his fierce pride and desire to prove himself better than other mere

men, has taken precedence over the many other motivations for his crime.

This article content is really unique and amazing.This article really helpful and explained very well.So i am really thankful to you for sharing keep it up..

ReplyDeleteBest motivational speaker