Illustration to the Story by D. Minkov

Telega (Wagon, Cart) With Wounded Soldiers

[Note: This posting is complemented by the posting of Oct. 4, 2022, my analysis of how George Saunders approaches treatment of this Chekhov story in his book A Swim in a Pond in the Rain]

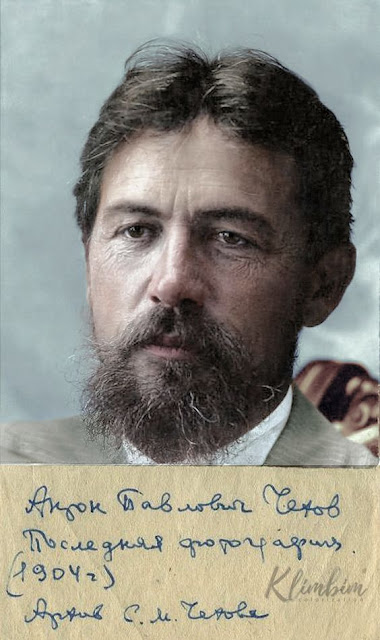

Anton Chekhov

На Подводе

(1897)

In

the Wagon

Critical Discussion

of the Story by U.R. Bowie

[Note: the story has appeared in English translation under a

variety of titles; I know of at least three: “The Schoolmistress” (Constance

Garnett trans.), “A Journey by Cart” (Marian Fell) and “In the Cart” (Avrahm Yarmolinsky,

the translation discussed by George Saunders in his book, A Swim in a Pond

in the Rain). My method, were I to be teaching this story in a course on

Russian literature: I would read the original first, then compare translations,

trying to pick the best one for my students to read. In quoting here from the

story in English I use the Marian Fell translation, which appears in the Norton

Critical Edition, Anton Chekhov’s Short Stories (edited by Ralph

Matlaw). I have made slight changes in certain passages and have changed her

title.]

d

The Structure of the

Story, the Protagonist, the Venality, the “Slice of Life”

The tale is structured around a journey. Chekhov likes to

write that kind of story. For one thing, you don’t have to worry about a

beginning or ending: the story begins when the journey begins and ends when it

ends. Most famously, and probably most successful of Chekhov’s trip fictions is

the long narrative tone poem, “The Steppe: A Story of a Journey” (1888).

Somewhat underappreciated amidst the author’s works, this remarkable

novella-length piece demonstrates Chekhov’s mastery of a poetic,

musically-based prose.

The main character of “In the Wagon”—a story of only nine

pages in the original Russian—is a schoolmistress, Marya Vasilievna, who lives

in the back of the beyond, apparently in the south of Russia, in a tiny hamlet called

Vyazovye. The story consists of her trip back from the main town in the

district, where she has gone, as she goes once a month, to collect her salary

and lay in a few comestibles (sugar and flour). The primitive cart she rides in

is driven by an old peasant, Semyon. We presume that she has hired him to drive

her there and back. She’ll pay him a ruble or two out of her salary of

twenty-one rubles and probably pick up the tab for the tea they drink at a

tavern on the way.

Note on Russian names: the protagonist’s last name is never

revealed. She is presented in the polite mode of address, by given name and

patronymic. The patronymic is the middle name, based always on the first name

of your father. Her father’s first name was Vasily, so she is a Mary (Marya)

daughter of Vasily (Vasilievna). For convenience in my discussion I refer to

her as MV. Her driver, old Semyon (this is his first name, English equivalent

is Simon) addresses her repeatedly by her patronymic, a peasanty, generally polite

but too familiar form of address. Were he to give her her due—she is, after

all, the only educated individual in the village, a woman of the gentry who deserves

respect—he should address her as Marya Vasilievna. But, as we are informed by the

narrator, she gets little or no respect from the peasants, who think that her

salary is too high (it is a pittance), and that she—like so many of them—finds ways

to skim off money from expenses, such as the wood that she has to acquire to

heat her small school and keep warm her five elementary-age peasant pupils: four

boys and a girl.

Funny thing about people who live their lives by cheating,

manipulating others, bribing, kick-backing, gaining favors through cronyism,

lying, stealing—this includes a multitude of Russians, to one degree or another,

not only in 1893 (tsarist Russia), but also in 1953 (Soviet Russia), or 1993 (transition

period into “New Russia”) or in 2022 (Putinist Russia). Such people usually

look with disdain on the rare person of probity. You’re a sap and fool if you

don’t play the game of corruption like everyone else. But once in a while—we’ll

encounter this in the tavern scene—such people put aside their cynicism and gaze

with genuine respect, marveling at the presence of a truly decent person.

Nothing much happens in the story under discussion; it’s a

typical “slice of life” narrative, describing a woman’s journey back to the

hamlet where she serves as schoolmistress. While riding she, mostly, worries

about her problems at the school, her difficulties with the ignorant watchman,

who disrespects her and beats the pupils, her problems with various other

peasants in positions of authority—which positions they have acquired through

graft or cronyism. She has complained repeatedly about the watchman, asked to

have him fired, all to no avail.

This “slice of life” story, for better or worse—often,

unfortunately, for the worse—is what Chekhov has contributed most saliently to

the short story tradition of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Why for

the worse? Because Chekhov was good at this sort of thing, but it’s hard to do

successfully; most imitators of Chekhov fail at it. Then again, now that we’re

into the second century of writing the “slice of life” business, the thing has

gone stale. Which means the reader faces masses of boring stories these days,

most prominently in The New Yorker, which specializes in such drivel.

Nature Description

The tale begins with a beautiful description of spring

coming on in the countryside. It is worth citing in full:

“The highroad was dry and a splendid April sun was beating

fiercely down, but there was still snow in the woods and wayside ditches. The

long, dark, cruel winter was only just over, spring had come in a breath, but

for Marya Vasilievna, driving along the road in a cart [URB: note that she is

riding в телеге, in a cart, not на подводе (in a wagon), the words

used in the story’s title; we will make much of this slight difference in names

of conveyances later], there was nothing either new or attractive in the warmth,

or in the listless, misty woods flushed with the first heat of spring, or in

the black flocks of birds flying far away across the wide, flooded meadows, or

in the marvelous, unfathomable sky into which one felt one could sail away with

such infinite pleasure.”

Here we depart briefly from the point of view of the main

character, MV, to breathe deeply and enjoy nature’s beauty on display. This is

certainly not MV, since she decidedly does not partake in this enjoyment, and

it is not us, the readers; we’re not there. So it must be the author, or the

representative of the author, he who narrates the tale. This violation of POV

is illegal in modern fiction-writing, but Chekhov does it only once, and we’ll

give him a pass this time. One more point: anyone who has read much of Chekhov’s

fiction knows that one of his favorite devices is to present a beautiful nature

description, by way of contrasting it to the sorry fortunes and/or bad morals of

the fiction’s protagonists. So it will be in this story.

The Tedium, The

Endless Rut, the Distress of a Decent Character Trapped in a Rut

“Marya Vasilievna had been a schoolteacher for thirteen

years, and it would have been impossible for her to count the number of times

she had driven to town for her salary, and returned home as she was doing now.

It mattered not to her whether the season was spring, as now, or winter, or

autumn with darkness and rain; she invariably longed for one thing and one

thing only: a speedy end to her journey.”

The next paragraph continues in the same vein, describing

how MV has been trapped in this back of the beyond for what seems like a

hundred years now, and she can visualize for her future nothing better than

“her school, and the road and the city, and then the road and her school again,

and then once more the road and the city.” Apparently of the gentry class, she once

lived a happy and varied life in Moscow, with her parents and brother. But that

was only in her childhood. Her parents are long dead, she has lost touch with

her brother, and nothing remains of that life except a photograph of her

mother, now so faded that only the eyebrows and hair are still visible. How did

she become a schoolmistress? Out of necessity. She probably attended a

pedagogical institute in Moscow, possibly helped with expenses by her brother,

an officer. Since she was an orphan, the state probably also provided a

stipend. But the recipient of such a stipend must accept a position in the

provinces or in a peasant hamlet, by way of paying back the government for what

she has received.

“In the Wagon” is a story about life in a dreary rut, an endless

trip back and forth over bad roads, from nowhere to nowhere. We don’t get the

“forth,” in this tale, only the “back,” but MV’s ride to the city would be just

the same tedious business. In other words, what we have here is quite the

typical Chekhovian mood story. If you’ve read much of Chekhov you realize that

MV fits right into a huge pantheon of disillusioned characters trapped in the

dreariness of what is life in the backward countryside, or in a provincial city

steeped in ennui.

All around MV, who is doing her best with a desperate

situation, are either underclass characters amenable to graft and corruption,

or the typical Chekhovian noblemen, who are educated and sensitive, but

hopelessly weak and ineffectual. Such among the latter is the landowner Khanov,

a man of about forty, who drives twice into the story in his fancy carriage,

pulled by four horses—once near the beginning and once again near the end. We

are told that Khanov lives at his large estate but does, essentially nothing.

He spends his time drinking, playing chess with an old servant, or walking back

and forth, from one end of a room to the other, whistling. This back and forth

movement echoes the protagonist’s monotonous back and forth trips on a cart to

the district town. Later we are told that Khanov’s way of walking somehow

imperceptibly betrays “a being already rotten at the core, weak and nearing his

downfall.”

MV finds Khanov attractive, would obviously like to be

around him socially, if not romantically. Like her, he is of the gentry class,

and, after all, she lives in a hamlet full of peasants, appears to have no

friends and not a single educated acquaintance. While his fine carriage,

driving ahead of her cart, labors through the muck of these typically Russian bad

roads, Khanov laughs off his predicament. She wonders why he, a rich man,

doesn’t spend some money to improve local roads, rather than tolerating the

mud. She also wonders why he doesn’t go and live in St. Petersburg, or even

abroad, instead of suffering in silence through his idle life in the countryside.

These are things that Chekhov also, obviously, wonders about. “What good do his

wealth, his handsome face, and his fine culture do him in this godforsaken mud

and solitude?”

MV imagines briefly falling in love with Khanov. “At night

she would dream of examinations and peasants and snowdrifts. This life had aged

and hardened her, and she had grown plain and angular and awkward, as if lead

had been emptied into her veins. She was afraid of everything, and never dared

to sit down in the presence of the warden or a member of the school board. If

she mentioned any one of them in his absence, she always spoke of him

respectfully, as ‘His Honor.’ No one found her attractive, her life was spent

without love, without friendship, without acquaintances who interested her.

What a terrible calamity it would be were she, in her situation, to fall in

love!” Then again, it may be a blessing in disguise that “no one found her

attractive.” A woman living alone and defenseless in Russia, even in today’s

Russia, is easy prey, as the #MeToo movement has made few inroads in that

largely patriarchal society. The situation could only have been worse 125 years

ago, when this story is set. In nineteen-century Russia peasant women and

governesses working in gentry households were always at the mercy of the

gentleman of the manor.

One more point about MV and her plight. The Marian Fell

translation contains an egregious error in translation, which shows up twice in

the text. Misreading one word, Fell has MV teaching in the peasant hamlet of

Vyazovye for thirty years (30!) instead of the correct thirteen. Which would

make her not a relatively young woman in her thirties but an aging creature in

her fifties. This is one reason why checking the English translation with the

original is so important for the teacher of Russian literature.

Background on The

Russian Social Scene of the Times

In this brief short story Chekhov describes in considerable

detail the tribulations of a country schoolmistress in 1893. A testimony to how

well he knew his facts is the reaction of his sister Masha’s schoolmistress friends,

who—as related in letters to Masha—described how they wept when reading the

story. Although MV’s truly terrible life is well presented by the narrative itself,

a look into Russian newspapers of the time—by Aleksandr Karsky in his critical

article, available online, in Russian—reveals just how desperate her situation

is.

As for Russian education of the time, Karsky reports

statistics from the year 1887. Of one hundred recruits taken into the army that

year, sixty-eight were totally illiterate (could not read or write). For Japan

comparative figures were 15.6 %. For France 5.7%, and for Germany .6%. Conditions

in a country school, such as MV’s, were hideous. An extremely bad winter of

1892-1893 had led to a shortage of wood for heating. People were chopping down

trees on state-owned property. Once even a whole barn was taken down, the wood

stolen (report in Voronezh newspaper).

MV has to ask her pupils for money to buy wood to heat her

school. She gets little help from corrupt peasant officials who are supposed to

provide the wood. Many peasants saw little reason for sending their children to

school, arguing that they were needed to do chores at home. In winter classes

hungry children would arrive at the school, having plodded several miles

through snow to get there. They would sit in class in coats and hats, unable to

write because the ink had frozen.

In 1891-1892 a horrendous drought in central and southern

Russia led to widespread famine. Nearly thirty million people lived in

conditions of starvation. In April of 1893, when the story is set, conditions

were particularly bleak, consequent upon the bad harvest of 1892. The sugar and

rye flour that MV buys in town were almost certainly brought in from somewhere

else, by philanthropic or government organizations. Much of it went to waste,

either stolen or stored carelessly. In his thoroughgoing analysis, Karsky goes

so far as to establish the price of sugar and flour, as regulated by the

government in light of the famine. MV would have had to expend a full month’s

salary toward her purchases in town, only to have the flour and sugar partially

spoiled by her driver Semyon’s stupid and bravado action. Rather than driving a

couple of miles out of his way, to where a bridge has been built, he decides to

ford the river, much swollen by spring rains; he could very well have drowned

his horse in harness. We readers were not there for the beginning of the

journey to town, but we cannot help wondering how Semyon got his cart and horse

across the river at the start.

Why, by the way, has the bridge been built several miles

from the village of Vyazovye? Early in the story we are told that Khanov is on his

way to visit his friend Bakvist’s estate. Near the end of the story he appears

again, crossing the bridge near that estate. The implication is that the

landowner Bakvist has used his influence, or bribed someone, to have the bridge

built conveniently near where he lives. Then again, why does the railway line,

described in the final pages, run through a backwoods hamlet, and not through

the most important district town? Once again, a bribe must have been involved.

Everything in Chekhov’s Russia ran on graft, corruption, cronyism. Sad to

report, but today, having lived through fifty years of corrupt Soviet rule, over

twenty years into Tsar Putin’s reign, Russia still operates almost exactly the

same way, corrupt from top to bottom.

N.A. Alekseev,

Moscow’s Outstanding Mayor (1852-1893)

Small details count for much in a Chekhov story. Semyon, who

likes to spread local gossip, mentions early in the story—this is, tellingly,

just before the first appearance of Khanov—that “They’ve taken down one of the

local officials in the town. Sent him off. So the rumor goes, he, along with

some Germans, killed the mayor of Moscow, Alekseev.” This detail, or course,

means little to the modern reader, in Russia or anywhere else, but it is based

on actual fact. I have Aleksandr Karsky to thank for digging deeper into the

episode, as well as elucidating a good many other points. The mayor of Moscow,

as Karsky informs us, was Nikolai Aleksandrovich Alekseev, shot and killed on

March 9, 1893. Apparently, Semyon’s bizarre tale about a local official

involved and the connivance of Germans in the murder is totally fabricated. But

the event did happen, and this allows us to pinpoint the exact date of the

action of “In the Wagon”: April, 1893.

Information about Alekseev is readily available online. So

we learn, he was an excellent administrator who did much to improve life for

citizens of the capital city. Under his administration pumping stations were

built, waterlines and sanitation improved, and open-air vegetable and fruit

markets were regulated so as to create better sanitary conditions.

Slaughterhouses were moved out of the city and Alekseev found novel ways to

battle against cholera outbreaks.

In addition to donating large sums of his own money, the mayor

deposited his yearly salary of 12,000 rubles into the city coffers. He issued a

number of city bonds and securities, and during his administration the city’s

assets were more than doubled; a deficit in the municipal budget was reduced

from 1.3 million rubles to zero. In his will he left 300,000 rubles toward the

establishment of a hospital, which was named after him. He was only forty years

old when murdered. The assassin turned out to be mentally disturbed, the same

kind of troubled individual so familiar to us in today’s U.S.A., where, due to

our insane gun laws, people like this perpetrate hideous violence almost on a

daily basis.

In Chekhov’s letters he expressed how upset he was to learn

of Alekseev’s murder, and four years later he included mention of it in his

story. He was asked by the publisher at the newspaper where the story first

appeared (Russkie Vedomosti) to remove the mention of the murder. This

in deference to Alekseev’s survivors—his mother, wife and three daughters—who would

find the detail disturbing. Chekhov complied, but in preparing the tale later

for inclusion in his collected works, he reinstated the original passage. He

must have really wanted this passage in the story. Why?

The answer is obvious. Here we have a subtle message about

how few are the real benefactors of humanity in Russia, honest and decent

people. How many, in contrast, are those, like the crazed assassin, who do

great harm to the country by destroying the benefactors. How many, as well, are

the graft takers, bribers and corrupt officials—most of the characters in the

story fit into that category—and the feckless types like the landowner Khanov,

who comes driving into the story immediately after this oblique allusion to

Alekseev.

Podvoda (Telega)

The Issue of the

Conveyances

For the twenty-first century reader it may be hard to

visualize what kind of vehicles Russians used to get around in the nineteenth and

early twentieth centuries. Even for today’s Russian urbanized readers these

conveyances are, largely, a thing of the past. I’ve tried to find images on the

internet to include with my discussion. MV is riding, as Chekhov tells us in

the first paragraph, в телеге (v telege), in a cart (wagon). A telega is the

most primitive of carts or wagons used in backwoods Russia, mostly to haul produce

or materials about. The very fact that this is what MV must use to get to the

district city and back tells us much about her penurious situation and her

status. By rights she, an educated woman of the gentry class should be riding

in proletka (a light carriage) or some other springed vehicle. The telega

has no springs and treats its passenger to an extremely rough ride.

Telega (Podvoda)

Given Khanov’s wealth and status as landowner, it is no

surprise that he is riding в коляске четверкой, in

a four-in-hand carriage, i.e., a carriage pulled by four horses, two harnessed

up front and two more behind them. Note that Khanov’s four-in-hand can cope

with the bad roads no better than the telega can. Bad roads are a

constant factor in Russian history, and even today—especially in the countryside—spring

rains bring on such muck as to make travelling close to impossible.

Traditionally in Russia spring roads are nearly impassable, summer roads mean

coping with dust, and the best time to travel is in the winter, when vehicles

have wheels replaced by runners and glide as sleighs over the ice.

Proletka

Four-in-Hand

The title of Chekhov’s story is “На подводе (Na podvode),”

which translates as “In the Cart,” or “In/On the Wagon.” Podvoda is

almost an exact synonym for telega, which leads translators, as well as

Russian critics, to assume that the title refers to MV sitting in her cart.

Maybe it does, but it’s worth mentioning that the title word shows up only once

in the body of the story, to describe carts/wagons standing outside the

pothouse in the village where MV and Semyon stop for tea. Here’s the passage:

“They arrived at Nizhni Gorodishe. In the snowy, grimy yard

around the tavern stood rows of wagons [podvody], laden with large

flasks of sulphuric acid. A great crowd of carriers had assembled in the

tavern, and the air reeked of vodka, tobacco, and sheepskin coats.” Since a

different word is used for the cart in which our protagonist rides (telega)

from the carts transporting the sulphuric acid (podvoda), I have decided

that a different word is proper for the title of the story in English. Not “In

the Cart,” where MV rides, but “In the Wagon,” where the bottles of acid ride.

Oil of Vitriol

Chekhov is a writer much concerned with daily problems in

his society at the time he wrote. He is not, however, given to preach social

change, advocate revolution, or rant and rave about the shortcomings of the Russian

social/political structure. He lets plain facts speak for themselves, does not

raise his voice. Certain specific detail, however, is there for the reader to

look at and consider. The details touch upon important issues, often in quite

subtle ways.

What is his point in using the title word only once in the

body of the story, to describe wagons transporting sulphuric acid, also known

as oil of vitriol? The detail must have special importance if so expressed. Consulting

contemporary newspaper articles, Karsky has investigated uses of oil of vitriol

at the time the story is set. This concentrated sulphuric acid was used to

produce starched sugar and yeast. If the proportions were incorrectly mixed—a

frequent occurrence in Russia—the acid could get into baked bread and people

were poisoned. Even more ominously, oil of vitriol was used in the production

of pyroxylin and nitroglycerine, which went into the making of dynamite in

factories but were also used by terrorists to produce bombs in underground

labs.

Only sixteen years before “In the Wagon” was published, in

1881, Tsar Aleksandr II was assassinated by a terrorist bomb. His son,

Aleksandr III has clamped things down again, but in 1893 revolutionary ferment is

by no means totally extinguished. It is to raise its ugly head again in the

events of 1905 and culminate only twenty years after the story was published:

in the bloodbath of the revolutions and Civil War that will lead to the

formation of the Soviet Union. Perhaps MV’s peasant students, the four boys in

her classroom, will participate directly in those tumultuous events.

Here, in what is somehow a typically Russian situation, we

have drunken peasants carting across provincial Russia the materials for making

bombs. Given the importance of this one detail, and given the fact that Chekhov

has emphasized its importance by using the title word, podvod only this

once in his story, I would suggest that a daring translator might go one step

further. To underline the ominous fact of the acid on the wagons, he/she might

call the story “Sulphuric Acid,” or “Oil of Vitriol.”

Conclusion

Chekhov was, and still sometimes is, labelled as a

pessimistic writer, one who leaves little hope for the disillusioned characters

in his stories and plays. Yet the way this story plays out, you can read it as

optimistic. The optimism lies in the fortitude of the heroine, who has every

reason to give up yet perseveres. This despite her being more of a drudge than

some sort of heroic figure.

“She had felt no calling to be a teacher; want had forced

her to be one. And she never thought about her calling, about what she was

doing for enlightenment. To her it always seemed that the most important thing

was not the pupils and their enlightenment, but the examinations. And when

would she have time to think about a calling or about her contribution to

enlightenment?”

Note the use of the word “enlightenment” three times in one

paragraph. Given the rules of fiction writing, this is a mistake, and the

translator Fell smooths over the passage—not only does she miss the repetition

of the word, but she never uses “enlightenment” even once; she prefers the

synonyms “education” and “instruction.” But perhaps Chekhov here is preparing

us for the scene of literal “enlightenment” to come, the epiphany near the end

of the story.

To continue quoting: “Struggling with their laborious tasks,

schoolteachers, poor doctors, medical assistants are deprived even of the

consolation of thinking that they serve some ideal or the people, since their

heads are all the time crammed with thoughts of a crust of bread, of firewood,

bad roads, illnesses. Life is tedious and hard. The only ones who can bear it

for long are silent beasts of burden like this Marya Vasilievna.”

Especially revealing is the scene in the tavern, where MV

and Semyon take a break for tea. Outside sit the wagons loaded with those

ominous bottles of oil of vitriol, while the drivers of the wagons are inside

getting drunk. Semyon shouts at one old man to watch his language: “Can’t you

see there’s a lady here?” This occasions a few drunken shouts of derision, but

the little peasant whom Semyon has rebuked is embarrassed. He delivers a

semi-apology to MV, wishes her a good day. Apparently at ease in the presence

of the peasants, MV “takes pleasure” in drinking her tea—the one time in the

whole story when she feels any pleasure—even though the same dark thoughts

revolve in her mind: “about the firewood, the watchman.”

At this point something unusual happens. These rough

peasants, many of them drunk, the same people who normally would disrespect an

educated person of the nobility, show a measure of respect for someone who

eschews venality and labors on honestly despite the drudgery of her task. One

of them says, “It’s the schoolmarm from Vyasovye. We know her! She’s a fine

lady.” Someone else echoes, “A decent lady!” When they get up to leave the

tavern these peasants, led by the meek little man, come by her table to shake

her hand.

Chekhov is a master at putting together little touches such

as this. Especially lovely is the passage right before the peasants leave: “The

door banged repeatedly, men came and went. MV sat absorbed in the same

thoughts, and the concertina behind the partition never ceased making music for

an instant. Patches of sunlight that were on the floor when she came in had

moved to the counter, then to the walls, and now had finally disappeared. So it

was already afternoon.”

Those bits of “enlightenment” in the sunspots are preparing

us for the bravura ending of the story, when an efflorescence of late-afternoon

light suddenly bathes MV and everything around her. Semyon has just completed

his reckless fording of the river, they are nearing the hamlet of Vyazovye, MV’s

precious flour and sugar are wet, as are her feet. She trembles all over from

the cold, but the fading afternoon sun

illumines her school with its green roof and the village church with its

gleaming crosses.

MV sees the train, whose windows are so glaring with

reflected light that it hurts her eyes to look at them, and then comes a sudden

vision. A lady is standing on one of the platforms of a first-class carriage;

MV glances at her in passing and then suddenly: “It’s mother! What a

resemblance! Her mother had the same sumptuous hair, the same shape of the

forehead, the way of holding her head.” This leads MV, for the first time in

thirteen years, to recall details of her happy childhood in Moscow, with

mother, father, brother. “Great joy and happiness suddenly welled up in her

heart, and she pressed her hands to her temples in rapture, crying softly with

a note of deep entreaty in her voice: ‘Mama!’

“Then she wept and could not have said why. At that moment

Khanov drove up with his four-in-hand, and when she saw him she smiled and

nodded to him as if he and she were equals and dear to each other, for she was

conjuring up in her fancy a felicity that had never been hers. The sky, the

trees, and the windows of houses seemed to be shining with her happiness, her

triumph. Yes, her mother and father had never died; she had never been a

schoolteacher; all that had been a long, strange, bad dream, and now she was

awake.”

So the story ends, with this brief epiphany on the part of

the main character. But not before she awakens back into the dreary reality of

her life. Semyon yells at her to get back in the cart, the vision vanishes;

shivering with cold, she sits down again and they cross the railway track into

the hamlet of Vyazovye.