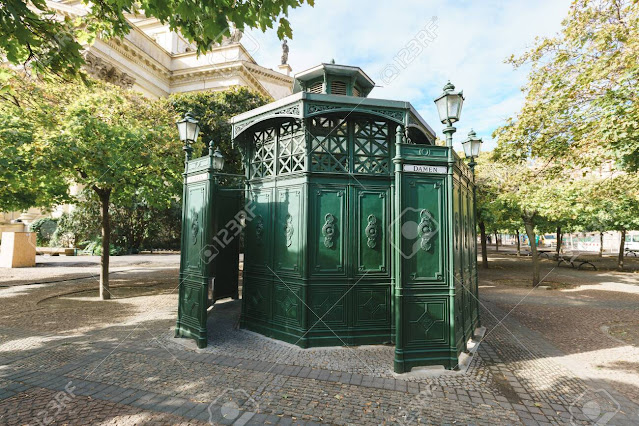

Old-Style WC in Berlin

Владислав Ходасевич

(1886-1939)

Под землей

Где пахнет черною карболкой

И провонявшею землей,

Стоит, склоняя профиль колкий

Пред изразцовою стеной.

Не отойдет, не обернется,

Лишь весь качается слегка,

Да как-то судорожно бьется

Потертый локоть сюртука.

Заходят школьники, солдаты,

Рабочий в блузе голубой, –

Он всё стоит, к стене прижатый

Своею дикою мечтой.

Здесь создает и рaзpушaeт

Он сладострастные миры,

А из соседней конуры

За ним старуха наблюдает.

Потом в открывшуюся дверь

Видны подушки, стулья, склянки.

Вошла – и слышатся теперь

Обрывки злобной пеpeбpaнки.

Потом вонючая метла

Безумца гонит из угла.

И вот, из полутьмы глубокой

Старик сутулый, но высокий,

В таком почтенном сюртуке,

В когда-то модном котелке,

Идет по лестнице широкой,

Как тень Аида – в белый свет,

В берлинский день, в блестящий бред.

А солнце ясно, небо сине,

А сверху синяя пустыня…

И злость, и скорбь моя кипит,

И трость моя в чужой гранит

Неумолкаемо стучит.

1923

d

Literal Translation

Underground

Where it smells of

carbolic acid

And the stench of earth,

He stands, his sharp

profile bent

Against the tile of the

wall.

He won’t step back, won’t

turn around,

Just slightly rocks all

over,

And the threadbare elbow

of his frock-coat

Somehow shudders convulsively.

Schoolboys come in,

soldiers,

A laborer in a light-blue

blouse;

He goes on standing,

affixed to the wall

By his bizarre daydream.

He’s creating here and

destroying

His own voluptuous

worlds,

And from the cubbyhole

next door

And old lady watches him.

Then through the opened

door

One sees pillows, chairs,

phials.

She has come in, and now

one hears

Fragments of a spiteful

squabble.

Then a stinking broom

Drives the crackpot out

of his corner.

And then, from out of the

depths of half darkness

A stoop-shouldered, but

tall old man,

Wearing such a

respectable frock-coat,

Such a once stylish

bowler hat,

Ascends the broad

staircase,

Like the shade Aida—into

the wide world,

Into the Berlin day, the

gleam of delirium.

And the sun is bright,

the sky is blue,

From high above there’s a

blue wasteland…

And my anger, my sorrow

boils up,

And my cane pounds away

Incessantly against the

alien granite.

d

Literary Translation/Adaptation by U.R. Bowie

Underground

The smell is disinfectant

phenol,

Combined with moldy stench

of earth.

He’s come here not for

reasons renal,

He pulls at pleasure,

forlorn mirth.

His profile bent, his

thoughts remote,

He leans against the wall

of tile,

The elbow of his worn

frock-coat

Is faintly trembling all

the while.

Schoolboys come in, and

soldiers too,

A workingman in

light-blue blouse;

He labors on in that sad

loo,

Rapt in his private

bawdyhouse.

A wild voluptuous

capriole

He’s leapt into with

rings of fire;

While from her next-door

cubbyhole

She peers with

ever-growing ire,

Then open wide she throws

the door,

That crone attendant—one

could note

The pillows, chairs and

phials, more;

Now she’s entered in full

throat,

The fragments of a spat

ring loud,

And with a broom that

reeks of muck

She routs the culprit, cringing,

cowed.

And then emerges the

rebuked,

From depths of gloom he

makes his way:

An old man tall, but

frail, stooped,

In what was once a frock-coat

gay,

In bowler erstwhile much in

style.

He slowly climbs the

broad stairway,

Aida’s ghost, in socks argyle,

He blends with Berlin’s

frenzied day.

The sun is clear, sheer

blue the sky,

An azure wasteland gleams

on high . . .

Inside me burn both grief

and spite;

As my cane pounds at

stone off-white,

I step, am steeped in gruesome

light.

d

Translator’s

Note

The poem is set in Berlin, Germany, 1923. The scene may need

explaining for American readers. When I was sent to Germany in the U.S. Army,

summer of 1964, the arrangement of public toilets was the same as described in

this poem. All over Europe things were set up much the same way, and probably

still are, for all I know. I suspect, however, that the public facilities in

Germany are cleaner these days.

1964. In a little annex when you first enter the men’s WC (often

below ground, as in this poem), an old woman sits, a toilet attendant. She is

there to keep things in order, to clean up occasionally—although cleanliness is

not usually much in evidence and the stench can be overwhelming. She provides

toilet paper when needed, as well as towels, often for a small fee. She has no

compunctions about being in the part of the WC where the urinals are, even

while male urinators go about their business.

The pillows, chairs and phials that the poet/narrator describes

when she opens the door to her cubbyhole are part of her daily arrangement of

things—her little world with her little things in the alcove, where she

presides over urination, defecation, and—in this case—illegal masturbation.

P.s.: Something I read recently in a book by David Sedaris (A

Carnival of Snackery: Diaries 2003-2020) leads me to believe that the

conventions of public toilets in Germany are much changed now from what they

were in 1923, or 1964. Sedaris (p. 45-46) describes what is apparently a

feminist campaign in 2004 to make men urinate sitting down in public toilets.

Entering a bathroom at a bookstore in Hamburg, he saw “an odd

sticker applied to the wall above the toilet. On it were two drawings. The

first showed a man in the act of peeing. He stood looking straight ahead, his

penis in his hand. Normal. This drawing was overlaid with a slashed red circle,

the international symbol for ‘No.’ The second drawing showed the same man

sitting with his pants around his ankles. It wasn’t elaborately detailed, but

you could sense that he was happier here, content that his actions, however

inconvenient, were making the world a better place.”

On the next page Sedaris quotes an article in a supplement to the International

Herald Tribune, “on the WC Ghost, a talking device that attaches to the

underside of a toilet seat and warns the user to sit down. ‘Peeing while

standing up is not allowed here and will be punished with fines,’ one of them

says. The ghost can be ordered with the voice of either Chancellor Schrōder or

his predecessor, Helmut Kohl, and the manufacturer sells two million a year. I

guess the Germans are really serious about this.”