Book Review Article

René de Saint-Denis, The Songs and Laments of Loōmos,

Laocoōn

Press, 2021, 128 pp.

With his Loōmos book the author attempts a

presentation of art as an integrated whole. As the subtitle tells us, “Text,

drawings, paintings, music and sculpture” are included here. We read the words

of the book, but, simultaneously, we interact with everything else. We, of course,

do not interact directly with the sculptures by Saint-Denis—here we must be

content with their visual representations. Nor do we hear the actual music, as

this is not an audiobook. But the final section, “Songs and Laments,”—four

separate pieces comprising a total of fourteen pages—consists entirely of

musical notations.

Therefore, in order to “hear” the music of the final section

you have to be a musician yourself, able to read the notes provided on paper.

The author may have considered publishing an audiobook, or including a CD of

the final section with this paperback. But then again, given certain unique and

avant-garde features of Loōmos, he may have deliberately

intended the final section not to be played. So as to achieve something

like what the composer John Cage created when he wrote his famous composition

consisting of silence. All the musicians sit in stillness on the proscenium, holding

their instruments, while the conductor stills his baton and all his

gesticulations. The “music” consists of isolated coughs and throat-clearings

from the audience, plus a few car horns blowing and ambulance sirens from the

outside world.

At any rate, this is a book of fiction with words, so we

read it, but we soon discover that it is to be read in ways not congruent with

the normal ways of reading a story for the plot or the sense of the text. The

book has, in essence, no plot, and the sound of the words is sometimes more

important than their meaning. Therefore, the reader rather drifts through the

text, communing simultaneously with the graphic imagery (the paintings,

drawings, sculptures on pages facing the text).

In the foreword R.G. Skinner explains how everything is

integrated into one harmonic whole. “[The] images often serve as a subtext, or

an alternate text running parallel with the literal text. In this sense the

work is also a kind of Emblem Book, in which the illustrations serve as emblems

or allegories of the text, commenting on them and creating a larger context of

association and meaning. In that there are characteristically single symbolic

episodes, they relate more to an unfolding situation, than to a consecutive

narrative.”

The scope of the project, the broadness of its intent, is

suggested by epigraphs to each of the individual sections. For example, the

page following the foreword includes epigraphs from Hesiod, Tennyson and

Chateaubriand. To cite only the last of these: “Our heart is a defective

instrument, a lyre with several chords missing, which forces us to express our

joyful moods in notes meant for lamentation.” Quickly skipping forward from the

age of antiquity into the twentieth century, such epigraphs (and thoughts in

the text) skim across, and sometimes delve deeply into the whole tradition of

Western philosophy and thought.

As for the text itself, it describes the wanderings of a man

named Loōmos,

born, apparently, in Greece, but exactly when we do not know. Inhabiting, for

the most part, no specific place or time, he has devoted his life to musing and

philosophizing. Here’s how the story begins (p. 3): “Beneath a brooding sky Loōmos

walked beside the Aegean, near his birthplace from long ago, watching the birds

play in the marsh grass, and the bees hover in amongst the rosehips. He was

content to move slowly about the dunes, looking around him as he went and from

time to time thinking about his life and the things he had seen and thought.

[paragraph break] In his lonely youth he studied philosophy, the sciences, and

mathematics, so that he might understand his place in the Universe.”

This is pretty much what the central—almost only—character

does for the whole rest of the book. This first page also suggests some of the

difficulties involved in reading the text. Here are mentioned, e.g., “the

aporias of the Megarians,” and “the Paradox of the Liar.” Then comes a

disquisition on numbers: “just as the sequence 0,1,2 . . . can never be

completed in the sense that it has no last member, the sequence . . ., -2,-1,0

cannot be completed in the sense that it has no first member, . . .” From this we

go on to “a logical paradox, much like Xenophanes’, which pitted the ideas of

infinite space and timelessness against those of finite space and time.”

That’s a lot to digest on one page, and only a reader who is

something of a polymath could cope with all the personages and ideas mentioned.

Take aporia. Look it up. In

rhetoric, an aporia is “a professing, or matter about which one professes, to

be at a loss what course to pursue, where to begin, what to say, etc.” Look up

“Megarian” and you learn that this pertains to Megara, a city in Ancient

Greece. The Megarian School was “a school of philosophers established at Megara

by Euclid, a disciple of Socrates, who taught that the good is one, and is the

only true being.” Xenophanes was an “Eleatic philosopher, noteworthy for his

emphatic (perhaps pantheistic) monotheism.”

None of this really get us very far, unless (the reader

suspects) one has a Ph.D. in classical literature or philosophy. At times we

drown in references to real or imagined personages. See, e.g., p. 30, the list

of sages come down from time immemorial, whom Loōmos decides to study:

“Oreastos, Xertis, Crosos, Practos, Zenaster, Reoem, . . .” etc., etc.—this

goes on much longer than one would hope. My trusty spell checker on the

computer puts red lines under all these names. Don’t know for sure, but I

suspect that some of these characters may even be fictitious, and that the long

list for effect is the most important thing here.

Sometimes it seems as if the author were inviting the reader

to research the many names dropped in the book. As if to say, “Here they are.

What, you don’t know who they are, the great thinkers of the Western (and

sometimes Eastern) world? If not, look them up!” Another possibility: by

drowning us in the mention of great men and great ideas—which men and ideas we

have never heard of—the author is reinforcing one of the central ideas of the

book: that human thought goes round and round but never really gets anywhere.

Logic is flawed, as Loōmos discovers early on. The

Logicians founder in the very logic they hold up as a beacon, wondering “if it

were not more a matter of infinite regress, a stalemate in a heretical game”

(41). Philosophy is suspect, and words are nebulous in their meanings. “But if

logic is defined as a theory of words, as opposed to a theory of meanings, and

words can be manipulated without reference to meaning, then discussion of his [Loōmos’s]thought

was futile, his words impenetrable, his questions sham, his doctrines false,

his ontology illusory, for perhaps he was, in truth, a Poet, and not a

Philosopher” (6).

But whether poet or philosopher, Loōmos is destined to operate

through use of the human brain, which itself uses, or attempts to use faulty

logic and faulty words. This is self-evident at the beginning of the book. The

modus operandi of Loōmos—thinking, philosophizing, trying to make sense of

things through manipulating words—is on shaky grounds. But he never falls

silent, and the esoteric references continue: “the gods merely saw images of

insoluble equations, or irrational numbers, of Ptolemaic epicycles inscribing a

fiction as illusory as the dialectics of Zenon of Elea, those stark, sunlit

days on the Tyrrhenian Sea.”

So mathematics, as the author implies here, also is a dead

end. I’m reminded of the recent book by Benjamín Labatut, When We Cease To

Understand The World, which describes—in semifictional terms—the travails

of the great physicists and mathematicians of the twentieth century, such as Karl

Schwarzschild, Alexander Grothendieck, and Werner Heisenberg, who were

constantly on the verge of mental breakdown as they wracked their brains to

understand how the universe operates.

Like these men, Loōmos is, for the most part, lost in the

loneliness of the deep thinker. Throughout the whole book he wanders about as

solitary pilgrim, walks along with words, concepts, notions, hand in hand with

thinkers of the past but isolated from his fellow human beings. At one point he

mentions “withdrawing into the turpitude of my aloneness.” Could be that the

silent music that shows up in the final section is emblematic of the failure of

words for Loōmos,

and for the whole human race.

His basic predicament is perpetual loneliness, due to his

“dark and humorless nature” and his eternal hopeless striving for knowledge.

There is nothing of the light touch about Loōmos, and since he is basically

humorless—as is the entire text of the book—he, and the reader, can hope for no

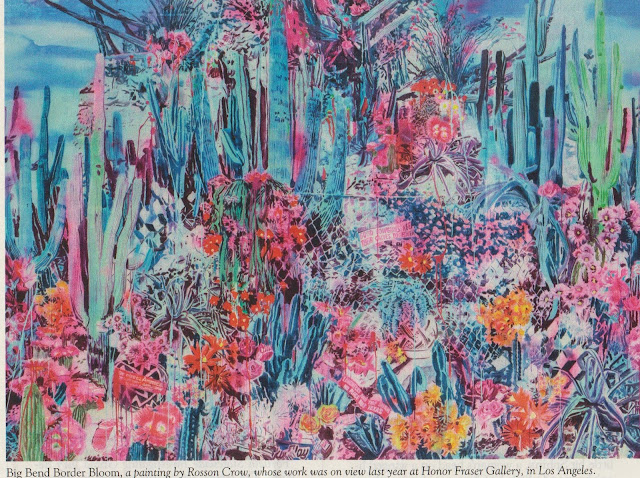

relief in passages leavened by humor. Some relief, however, is provided by the

beautiful illustrations placed on pages facing the text. For the most part

these paintings are not directly relevant to the matter at hand. An exception

comes when the text mentions “a young girl kneeling before a woman dressed in

white,” and the painting on p. 34 shows us that girl and the woman in white.

The conversation here, between the woman—a kind of pseudo guardian angel—and

the girl, calls into question belief in a loving God. This is reinforced by the

epigraph from Jean Paul: “God is dead! The sky is empty . . . . Weep! Children,

you have no more father!”

Few conclusions are evident, or even possible. “Loōmos

slowly began to reach certain conclusions, which he tried to formulate in

everyday language,” but this, of course, goes against the grain of the whole

book’s style. “As he consolidated his thoughts, he sensed the inadequacies of

placing his ideas in ordinary language.” That, maybe, is a key sentence in the

book as a whole, where the language, steeped in the lushness of Romanticism, is

far from ordinary. And this: “He was aware of his turgid language, but found

that, at present, it best expressed his ideas.”

For the reader of this book it soon becomes obvious that

there are things more important than the literal meanings of words in passages:

the feel and sound of those words, their interaction with the graphic art

surrounding them and with the silent music of the final section. One can quote

numerous passages in which words appear to abandon their thrall to meaning;

looking to make much sense of such passages gets you nowhere.

“The Angels would recoil, and mime those parabolas through

which Mind sought to merge with the celestial spheres, and in that way give

form to the elemental opposites; for as the gods stood over and above the

Fates, the Angels would remain to further enforce the emulation or immolation

in the name of ‘received’ truths” (25).

“Rapt attention was paid to the entrance made by the

Temptations, a bouncing-off or reverberation following certain tendencies

established at a time mired in superstition, and anticipating Thomist ideology

stolen piecemeal from Averroës and Maimonides, who borrowed in turn

from pre-Socratic effusions via Plato and a recalcitrant Aristotle” (33).

“When at last alone again, balanced precariously between the

abyss and the teeming gardens of Dionysus, Loōmos felt a transcendent

madness in response to this enraptured solitude. Then the gods began appearing

singly and in pairs, giving rise to rumors of a Heaven lost to hopelessness;

and, in temporary residence, their defilements fed one upon the other in

increased ratio to the good desired from their encroachments. The Sun rose

again and contrasted sharply with these febrile offerings, rantings which, from

the mouths of gods, were savored as rare obloquy” (65).

d

The Songs and Laments of Loōmos probably fits best

into a long tradition of experimentation in Western literature—especially since

the Age of Modernism began (late 19th and early 20th

centuries). Impossible to grasp, the exact sense in passages such as those

cited above spills over into something like trans-sense. The trans-sense, or

trans-rational movement in Russian literature of the early twentieth century

was probably inspired by avant-garde literary movements in France and Germany.

Dadaism, e.g. was an important influence for the Russian Futurists, and probably

also for René

de Saint-Denis. “The works of French poets, Italian Futurists and the German

Expressionists would influence Dada’s rejection of the tight correlation

between words and meaning” (quote from Wikipedia article on Dadaism). Modernist

art prefers multiple viewpoints and discontinuous narratives. Sometimes artists

prefer obscurity to lucidity. Unity is mistrusted. So it is with Saint-Denis.

In an article on trans-sense literature, called ZAUM, the

Russian critic Viktor Shklovsky cited the 19th century poet Fet: “Oh

if only one could express/One’s soul without words.” Shklovsky’s article

continues as follows: “Thought and speech cannot keep up with what an inspired

man experiences; therefore, the artist is free to express himself not only in

ordinary language (concepts), but also in a personal language, a language that

has no precise meaning (that is not ossified), that is trans-sensible.

“Ordinary language restricts, free language allows freer

expression. Worlds die, the world is always young. The artist has seen the

world anew and, like Adam, gives to everything its name. The lily is wonderful,

but the word lily [lilia in Russian] is ugly; it is worn out and

‘raped’ So I name my lily euy and the original purity is restored.”

Shklovsky cites examples of experimentation that wrenches language out of its

norms from many different writers, such as this one from Kingsley Amis, to be

read in a Texas drawl: “Arcane standard Hannah More. Armageddon pierced staff.”

Meaning: I can’t stand it any more; I’m getting pissed off.

The Russian Futurist poets—most prominently Velimir

Khlebnikov and Aleksei Kruchenykh—wrote entire poems in incomprehensible (trans-rational)

language. Their aim was to “liberate sound from meaning to create a primeval

language of sounds.” Of course, their “tampering” with language caused a furor

in their time, and they were accused of babbling nonsense. People with meat and

potato brains screamed, “This is bullshit!” Meat-and-potato-head readers of René

de Saint-Denis today, no doubt, will voice similar sentiments.

One more quote from Shklovsky’s article (which is available

in English translation online): “Some people assert that they can best express

their emotions by a particular sound language that often has no definite

meaning but acts outside of or separately from meaning, immediately upon the

emotions of people around them.” A good deal has been written since the early

20th century on this sort of thing. William Empson, e.g., in his Seven

Types of Ambiguity, has mentioned “the doctrine of pure sound,” which

assumes that speech sounds in themselves have meaning. Artists steeped in

Modernism sometimes use obscurity as a conscious strategy. That want to avoid

having their works consumed and digested too easily. Everyday language is

suspect, as it can no longer be a medium for truth. Having grown stale and

threadbare, the language of the quotidian must have violence wreaked upon it—only

by suffering violence can it yield something novel, something of value.

Writers doing similar things in our time keep popping up.

Take Joy Williams. In a recent article in The New Yorker (Sept. 27,

2021), Katy Waldman writes that reading the short stories of Williams is “like

climbing an uneven staircase in a dream.” Her stories “offer a dark provisional

illumination, and they make the kind of sense that disperses upon waking.”

“She [Williams] seems especially attuned to the

psychoanalytic distinction between ‘manifest’ and ‘latent’ content—the smoke

versus the fire beneath it. In ‘The Farm,’ from 1979, a woman utters words as

‘codes’ for other words, terrible words.”

“One of the strangest parts of reading Williams is the

jumpiness of her language, a feeling that her nouns and verbs, no matter how

meticulously ordered, might be arbitrary, a ‘code’ for things impossible to

say.” Here we are reminded, once again, of René de Saint-Denis, although his

literary style is not characterized by ‘jumpiness’ and little resembles that of

Joy Williams. Williams practices what Katy Waldman calls a kind of

“hallucinogenic realism.” The hallucinations of René de Saint-Denis—if that’s what

they may be called—are far from realism, are, in fact, more akin to

Romanticism.

The style of writing in the Loōmos book recalls the lushness

of the Romantic school; more likely it comes, however, out of the Neo-Romantic

school (Modernism, Symbolism) that was born as a rebellion against the stark,

unadorned Realism that preceded it. Throughout the whole book that features him

as central character, Loōmos ambulates through the verdure of perpetual opulent and

sumptuous language—but language whose meaning is less important than its

lushness.

As Waldman is led to assert through her reading of Joy

Williams, “If a new story is possible it will require an entirely different

language; the current one has been desecrated with the climate.” This recalls

Shklovsky’s mention of how words have been used, “raped.” Food for thought. As

the climate worsens, as we continue raping the natural world and the human race

descends toward an Armageddon of its own making, is the only legitimate

language left for literary writers one of experimentation—one practiced by

avant-garde belletrists such as Williams and Saint-Denis?

Maybe more and more frequently we will encounter literary

movements such as the recently founded “Poetry of Extinction.” Writers

belonging to this movement make it their task to write “audio-poetry” that

embodies the sounds of extinct animals. Most recently they have

produced—reproduced in poetic form—sounds emitted by the ivory-billed

woodpecker as recorded in 1935. This “poetry,” plus photographs and videotapes,

are all that we have left of the ivory-billed, a woodpecker (related to the

pileated) who was once the largest woodpecker resident in the U.S.A. The last

confirmed sighting of the ivory-billed was in 1944.

No comments:

Post a Comment