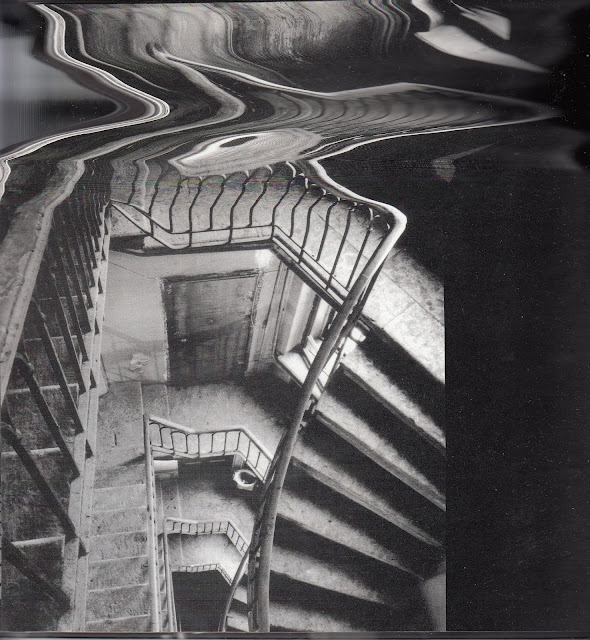

Staircase in St. Petersburg

The Atmosphere of Crime and Punishment: the Decadence of

the “Petersburg Spirit”

I find it interesting that C and P is set in mid-summer, a time of bounteous sunlight and

warmth in St. Petersburg. When I’m reading this somber novel I always have the

feeling that I’m trekking through the St. Petersburg of autumn, with its chill,

its cold rain and darkly oppressive air.

“It is possible to speak if not of a school then surely of a

Petersburgian genre in Russian literature, of which Dostoevsky is in fact the

leading practitioner. Pushkin’s The

Bronze Horseman is doubtless the outstanding poem in that genre, as Gogol’s

“The Overcoat” is the outstanding story and C

and P the outstanding novel.” In Russian literature the Petersburg Spirit

embodies, largely, gloom, angst, the uncanny and macabre.

“Dostoevsky describes the metropolis in somber colors,

taking us into its reeking taverns and coffin-like rooms, bringing to the fore

its petty bourgeois and proletarian types, its small shopkeepers and clerks,

students, prostitutes, beggars and derelicts. True as this is, there is also

something else in Dostoevsky’s vision of Petersburg, a sense not so much of romance

as of poetic strangeness, a poetic emotion attached to objects in themselves

desolate, a kind of exaltation in the very lostness, loneliness and drabness

which the big city imposes on its inhabitants.”

Philip

Rahv, “Dostoevsky in Crime and Punishment”

Dostoevsky was always fascinated by the Haymarket District,

one of the slummiest parts of the city in the mid-nineteenth century, with its

center on Haymarket Square (Сенная площадь). Here

is where Raskolnikov went down on his knees and kissed the earth on his way to

confess the murder. In the 1860s Dostoevsky lived in this area, on the corner

of Carpenter’s Lane and Little Tradesmen Street. His daughter Lyubov—who was in

her own right a character out of a Dostoevsky novel—later described him as

roaming about Petersburg in the 1840s, “through the darkest and most deserted

streets . . . . . He talked to himself as he walked, gesticulating and causing

passersby to turn and look at him.” This makes a good story, but Lyubov probably

relied mostly here on the idle rovings of characters out of her father’s works.

In Dostoevsky’s time the Haymarket area had the highest

population density in the city. “A local landmark nicknamed the Vyazemsky

Monastery was a great block of slums owned by Prince Vyazemsky, which served as

the location of the Crystal Palace tavern in C and P” [Adele Lindenmeyr article

in Dostoevsky: New Perspectives, p.

100]. There were eighteen taverns on Raskolnikov’s small street [Srednaya Meshchanskaya

Street (Little Tradesmen St.)]. In 1865 an official government commission was established

to investigate the overcrowding, disease, drunkenness and immorality of the Haymarket

District.

After the emancipation of the serfs in 1861 peasants

migrated to the city, looking for work. This influx strained he city’s already

inadequate water supply and health services. Sanitation was bad. There were

cholera epidemics. Into the Soviet period, and even after, the city had a

reputation for bad drinking water. After one of Raskolnikov’s fainting spells

(Part 2, Ch. 1) he comes around to find himself “sitting in a chair, supported

by some person on his right, with somebody else on his left holding a dirty

tumbler filled with yellowish water.” Yellow, incidentally, is one of

Dostoevsky’s favorite colors in C and P,

emblematic of the psychic malaise that pervades the novel.

You can still get a pretty good idea of the way things

looked in the 1860s if you wander today around the so-called достоевские места (places

associated with Dostoevsky, located mostly in close proximity to the Griboedov Canal). Certainly most of the taverns and dives are gone,

as are the houses of prostitution, but there is still that same grimness of atmosphere,

which has nothing in common with the architectural splendor of the area down by

the Neva River, with its Russian baroque or neoclassical buildings. As late as

the Soviet period you could still visit the prototype for Raskolnikov’s little

coffin of a room, although I doubt if this is possible anymore. A photo taken

out of that window provides the cover art on the Norton Critical Edition of C and P.

In Part 6, Ch. 3, Svidrigailov lectures to Raskolnikov on

the Petersburg Spirit: “I am sure lots of people in St. Petersburg talk to

themselves as they walk about. It’s a town of half-crazy people. If we had any

science in this country, the doctors, lawyers and philosophers could conduct

very valuable research in St. Petersburg . . . . There are few places that exercise such

strange, harsh and somber influences on the human spirit as St. Petersburg.

What can be accomplished by climate alone!”

Sometimes you wonder how much of the malaise belongs to the

spirit of the city, and how much of it is Dostoevsky’s own malaise, which he

imposes on the city. Here is a description of Raskolnikov out on the streets,

greedily breathing “the dusty, foul-smelling, contaminated air of the town,”

listening to street singers (Part 2, Ch. 6):

“’Do you like street singing?’ asked Raskolnikov of a

passerby, no longer young, and with the look of an idler, who had been standing

by him near the organ-grinder. The man looked oddly at him, in great

astonishment. ‘I do,’ went on Raskolnikov, with an expression as though he had

been speaking of something much more important than street singing; ‘I like to

hear singing to a barrel organ on a cold, dark, damp autumn evening—it must be

damp—when the faces of all the passersby look greenish and sickly; or, even

better, when wet snow is falling, straight down, without any wind, you know,

and the gas-lamps shine through it.”

Here we have an aesthetic exultation in

slime, something about Raskolnikov’s sick soul that recalls what he once said

about his strange fiancée: “I probably would have loved her even more, had she

been lame or hump-backed.”

Among Russian writers Dostoevsky is probably best at

describing how something in the human soul can derive artistic inspiration, not

only from the beautiful, but also from the deformed and perverse. With the Decadent

and Symbolist literary movements of the late 19th and early 20th

centuries came a lot of writers who portrayed this artistic exaltation of the

squalid. Dostoevsky was their precursor, although he was officially still part

of the school of Russian Realism.

No comments:

Post a Comment